In 2015, during his MusiCares Person of the Year speech, Bob Dylan declared: “Everything was all right until Kristofferson came to town. Oh, they ain’t seen anybody like him. He came into town like the wildcat that he was, flew a helicopter into Johnny Cash’s backyard, not your typical songwriter. And he went for the throat… You can look at Nashville pre-Kris and post-Kris, because he changed everything.”

Forty-nine years earlier, while 25-year-old Dylan recorded his seminal double album Blonde on Blonde, 30-year-old Kristofferson worked as a janitor at Columbia Records, clearing ashtrays and cleaning the studio. The year before, he had forsaken a promising army career, relinquished the opportunities that came along with his Rhodes Scholarship, and been disowned by his illustrious family for shattering their expectations. He wholeheartedly embraced “bum-hood” in Nashville, embarking on a path to immortality and glory surpassing any general’s ambitions.

Kristofferson passed away peacefully in Maui, Hawaii, on September 28, at 88. His death marked more than the loss of a music legend and movie star; it was the passing of one of popular culture’s most fascinating figures, whose life was the stuff of myth and legend. He was among the greatest songwriters to ever pick up a guitar and sing the song of humanity. Labelling him merely an icon of country music would do his genius a disservice; Kristofferson’s songs, performed by artists across various musical traditions, became signature tunes transcending genre barriers. Blues singer Janis Joplin made “Me and Bobby McGee” entirely her own, while rock ‘n’ roll legend Jerry Lee Lewis popularised “Once More With Feeling” before Kristofferson ever played it live. “Help Me Make it Through the Night” has been reinterpreted by generations of musicians, each giving new expression to the classic.

Also Read | Do you hear the people sing?

Alongside Johnny Cash and Willie Nelson, Kristofferson propelled country music to its next evolutionary stage, freeing it from traditional constraints and universalising the art form. Even the “Man in Black” himself, Johnny Cash, acknowledged Kristofferson’s influence: “I think Kris changed country music a lot and made other songwriters sit up and pay attention. Made them work at their art, rather than just rhyming words and using catch phrases and clichés… He made me want to write better songs.”

Taking country music out of its comfort zone

Filmmaker Michael Cimino, who directed Kristofferson in the ill-fated Western epic Heaven’s Gate (1980), said: “Some of the lyrics he has written are as much a poetic evocation of the spirit of the American landscape as some of our best poetry. He is a poet who has responded to the American experience.” While Kristofferson’s songs were set against the American backdrop, their universal themes, emotional honesty, and simple conveyance made them timeless and perpetually relevant.

He chronicled the everyday struggles and seemingly insurmountable odds faced by ordinary, unsung people. His lyrics captured laughter and joy in the shadow of sadness and isolation, celebrated small victories amid larger defeats, and explored love, loss, heartache, and redemption. Above all, he championed the vitality of living in the moment:

“Well, I woke up Sunday morning

With no way to hold my head that didn’t hurt

And the beer I had for breakfast wasn’t bad

So I had one more for dessert

Then I fumbled through my closet

Found my cleanest dirty shirt

Then I washed my face and combed my hair

And stumbled down the stairs to meet the day”

(‘Sunday Morning Coming Down”, 1969)

Kristofferson’s songs inhabited the murky, tragic universe of country ballads: smoke-filled barrooms, hard-luck tales of broken men, cuckolded husbands, wronged women, and lost innocence. In this world, moral lines blur, femmes fatales lurk, and the devil smiles behind expensive whiskey. The scent of sweat and sex permeates as characters surrender to temptation:

“Her smile was like the blindin’ light of sunshine on the snow

And the flashin’ of her hair was black as sin

And her body set the smokes of hell a-boilin’ in my skull

When the fiddle of the devil made her spin”

(“Stagger Mountain Tragedy”, from the album Border Lord, 1972)

Yet his lyrics also portrayed a world of profound compassion, where small kindnesses matter and happiness transcends monetary value:

“One truck driver called to the waitress

After the kids went outside

‘Them candies ain’t two for a penny’

‘So what’s it to you?’ She replied

In silence they finished their coffee

Then got up and nodded goodbye

She called, ‘Hey, you left too much money’

‘So what’s it to you?’ They replied”

(“Here Comes That Rainbow Again”, 1982)

Kristofferson crafted a realm of warmth and companionship, where sex was not taboo and human touch could banish the darkest nights:

“I don’t care who’s right or wrong

I don’t try to understand

Let the devil take tomorrow

Lord tonight I need a friend

Yesterday is dead and gone

And tomorrow’s out of sight

And it’s sad to be alone

Help me make it through the night”

(“Help Me Make it Through the Night”, 1970)

Despite his upper-class education, English literature degree from Merton College, Oxford, and passion for William Blake’s poetry, Kristofferson initially struggled with the rough-edged voice of country lyrics. Once he mastered it, however, he became untouchable in songwriting. His greatness stemmed from the simplicity of his style and the truthfulness of his message.

Kristofferson’s upbringing seemed ill-suited for the renegade, rambling poet of country music he would become. Born June 22, 1936, to a military family (his father was a two-star major general in the US Air Force), he excelled academically and athletically. Featured in Sports Illustrated in March 1958, he became an Air Force captain and competed in Golden Gloves boxing. His path seemed set for a military career and potentially political office.

Johnny Cash’s influence

Everything changed when Kristofferson saw Johnny Cash perform in Nashville. Cash was the most “driven, self-destructive, exhilarating” artist young Kristofferson had ever seen, and he longed to emulate him. Years later, he quipped, “I was expected to at least become the Secretary of State; instead of a bum; which is what I am,” jokingly imitating Marlon Brando’s famous scene in On the Waterfront:

“See him wasted on the sidewalk in his jacket and his jeans

Wearin’ yesterday’s misfortunes like a smile

Once he had a future full of money love and dreams

Which he spent like they was going out of style

And he keeps right on a changin’ for the better or the worse

And searchin’ for a shrine he’s never found

Never knowin’ if believin’ is a blessin’ or a curse

Or if the going up is worth to coming down.”

In 1965, Kristofferson left his English teaching position at West Point and moved to Nashville. His friend’s aunt, songwriter Marijohn Wilkin, gave him his first contract at Buckhorn Music. To make ends meet, he worked odd jobs, including construction, railroad work, and bartending. He later became a janitor at Columbia Records to get closer to the music industry.

Kristofferson attempted to get his music to Johnny Cash through June Carter. Though June passed on Kris’s tapes, Cash didn’t listen, and they ended up at the bottom of his private lake with other aspiring artists’ recordings. Undeterred, Kristofferson later landed his helicopter in Cash’s backyard to deliver his recordings personally, sparking a friendship that lasted until Cash’s death in 2003. Cash would go on to perform several Kristofferson-penned songs, including “Sunday Morning Coming Down”, which topped the Hot Country Singles chart in 1970.

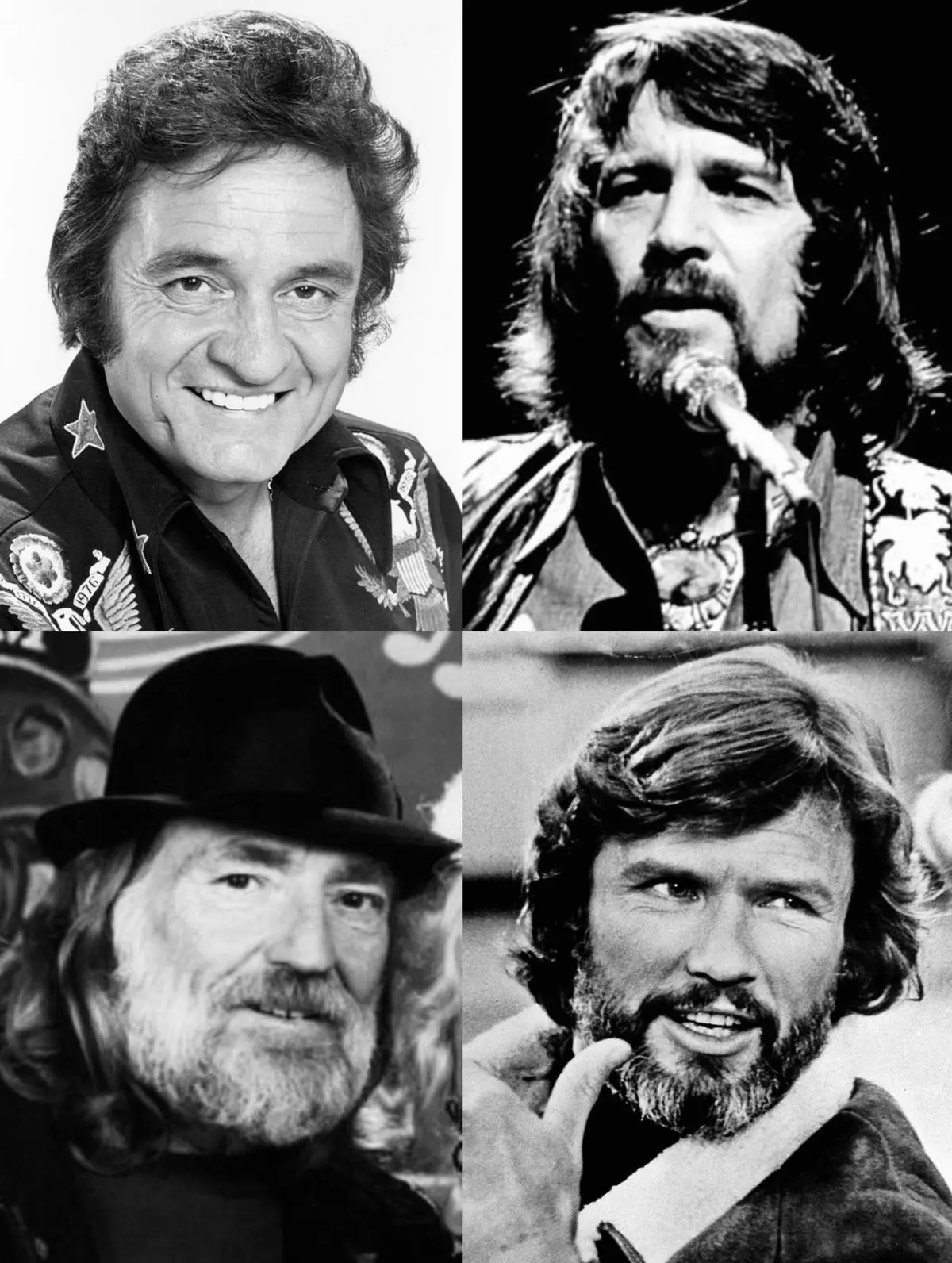

The Highwaymen, one of country music’s greatest supergroups. (clockwise from top left) Johnny Cash, Waylon Jennings, Kris Kristofferson, and Willie Nelson.

| Photo Credit:

Wikimedia Commons

Kristofferson’s first taste of success came in 1966 with “Vietnam Blues”, a pro-war song he later regretted writing. His breakthrough arrived in 1969 when three of his songs, performed by others including Jerry Lee Lewis, hit the charts.

Around this time, he met Fred Foster, founder of Monument Records. Impressed by Kristofferson’s songs, Foster agreed to use them if Kristofferson would record an album. Though Kristofferson did not consider himself a singer, his eponymous debut was released in 1970, featuring 12 tracks including “Me and Bobby McGee”, “To Beat the Devil”, and “Help Me Make it Through the Night”.

Despite his late start, Kristofferson became an icon of popular culture over the next 50 years. Along with Willie Nelson, Cash, Merle Haggard, and Waylon Jennings, he spearheaded the “Outlaw Movement” in country music, breaking from tradition to forge a path of creative freedom. Kristofferson, Cash, Jennings, and Nelson later formed The Highwaymen in the mid-1980s, one of country music’s greatest supergroups. With Cash and Jennings gone, only Kristofferson and Nelson remained—the last outlaws, revered for their work and anti-establishment stance. They eschewed stardom’s trappings, living life on their own terms. Now only Nelson remains, having turned 91 this year.

“Freedom’s just another word for nothin’ left to lose

Nothin’ ain’t worth nothin’, but it’s free

Feelin’ good was easy Lord, when Bobby sang the blues

Feelin’ good was good enough for me

Good enough for me and Bobby McGee”

(“Me and Bobby McGee”)

Movie star

While many music stars have appeared in films, few have been considered serious actors. Frank Sinatra, with his Oscar for From Here to Eternity (1954), was an exception until Kristofferson arrived. With his tremendous screen presence, Kristofferson held his own against the greatest actors of his time. He starred in iconic films of the 1970s and 80s, including Sam Peckinpah’s Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1973) and Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia (1974), Martin Scorsese’s Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore (1974), Frank Pierson’s A Star is Born (1976), Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate (1980), the neo-noir Trouble in Mind (1985), and the blockbuster Blade franchise. Kristofferson appeared in over 110 movies, successfully balancing both his music and acting careers well into his 80s.

Kristofferson’s rugged good looks and piercing blue eyes cut a striking figure on stage and screen. As he aged, his weather-beaten visage reflected the truth and wisdom of every song he had written, like a quality guitar gaining richer tones with each passing decade, proudly bearing the scars and dents that contributed to its greatness.

Also Read | Shakti: Still jamming with joy, still making history

His life was nobly lived, never compromising his convictions. His anti-right-wing stance often hindered his success, but neither deterred nor disheartened him. “I found there was significant lack of work after I did concerts for Palestinian children… but if that’s the way it has got to be, then that’s the way it has got to be,” he once said. Like the lovable bums, lonely misfits, and romantic outlaws populating his songs, Kristofferson never surrendered his dreams, remaining unvanquished to the end.

“But if this world keeps right on turning for the better or the worse

All he ever gets is older and around

From the rocking of the cradle to the rolling of the hearse

The going up was worth the coming down

He’s a poet he’s a picker he’s a prophet he’s a pusher

He’s a pilgrim and a preacher and a problem when he’s stoned

He’s a walking contradiction partly truth and partly fiction

Taking every wrong direction on his lonely way back home.”

From the wildcat who flew into Johnny Cash’s backyard to the weathered sage who departed this world, Kristofferson remained true to his contradictions—the Rhodes Scholar turned Nashville rebel, the military scion turned counterculture icon—proving that in America’s songbook, it is the oddballs who pen the catchiest tunes, their verses lingering long after the jukebox stops spinning.