In the latest Assembly session, Tamil Nadu Chief Minister M.K. Stalin unveiled plans for a memorial hall in Tharangambadi (formerly Tranquebar) to honour Bartholomäus Ziegenbalg, the founder of the Protestant mission in India. This memorial will celebrate his remarkable contributions to Tamil literature, ensuring his legacy endures for generations to come.

Ziegenbalg translated the Bible into Tamil and some Tamil didactic texts into German. He is also known for procuring and introducing a printing press from Europe to publish his materials. However, Ziegenbalg’s profound impact lies in his courageous act of integrating “pariahs”—the suppressed “outcasts”—into his residential mission school. By fostering unity and learning among students of diverse castes, he sowed seeds of inclusion, equality, and social justice. It was truly revolutionary considering the social norms of early 18th-century South India.

For these unsolicited efforts, Ziegenbalg faced criticism both in India as well as in Europe. While caste Hindus accused him of defiling local codes of social hierarchies and interactions, Europeans criticised his empathy towards Tamilians, arguing that missionaries should eradicate heathenism and not spread what they considered “heathen nonsense” in Europe.

A mission to Tranquebar

In 1705, Frederick IV, the King of Denmark and head of the Lutheran mission, commissioned two young students from the University of Halle, Germany, to establish a mission and spread Christian knowledge in Tranquebar. After several months at sea, the duo—24-year-old “fiery” Ziegenbalg and 29-year-old “calm” Heinrich Plütschau—reached Tranquebar in July 1706. By then, this small port town on the Bay of Bengal had been under the control of the Danish East India Company for almost 80 years. They acquired this territory after signing a treaty with the local Nayaka chief of Thanjavur, Raghunatha, in 1620.

Also Read | Tamilology and a German quest

After the decline of the Nayakas (dynasty present in South India during 1529-1736), Tranquebar came under the suzerainty (control) of the Thanjavur Marathas. The town had already acquired a cosmopolitan appearance due to its longstanding trade relationships with various parts of the world. Various racial, linguistic, religious, and ethnic groups resided in close proximity. Among them were Portuguese, English, French, German, and Danish-speaking Europeans; Arabic-speaking Muslims; Tamil and Portuguese-speaking Eurasians (descendants of Europeans and local women); and the larger group of Malabarians—the Tamilians.

Upon his arrival, Ziegenbalg encountered a surprisingly hostile reception from the Danish East India Company authorities. He was not allowed to enter the territory, and when he did so, he was thrown into jail for a few months. His contentious relationship with the Company persisted for several years.

Similarly, his attempts to establish a relationship with the Thanjavur king failed as the king refused to entertain European missionaries entering his walled city.

Following the Protestant tradition in Europe of establishing residential schools for the underprivileged, Ziegenbalg founded schools and developed a congregation. His initial congregants were slaves he purchased. The use and purchase of slaves, primarily from the “Pariah” castes, by landlords, traders, and Europeans was a common practice in this region. His congregation gradually expanded with the support of slaves, Eurasians, “Pariahs”, and Shudra Malabarian followers, many of whom had secured employment in European establishments. The Danish government and various Christian societies in Europe provided financial support for his activities.

Printing press on display at Ziegenbalg House in the coastal town of Tranquebar.

| Photo Credit:

Moorthy. M / The Hindu

Ziegenbalg spent a remarkable 13 years in Tranquebar. Upon beginning his work, he realised the necessity of two-way communication. As much effort as he took to convey the Protestant message of love, piety, and equality to the Tamilians, he had to exert the same effort to dispel the prejudices of Westerners about Malabarian society. At a certain point, he began to argue that there was no difference between the worldview of the Christians and that of Tamilians. His training in classical languages helped him to effortlessly master the Tamil language in a short span. Alakappan, his Tamil teacher, assisted him in procuring many rare Tamil books. A curious individual with a scholarly disposition, he sought knowledge from all corners. Beyond the Danish colony, he embarked on frequent journeys, engaging in spirited discussions with local poets, Brahmins, Muslims, and everyday folk, all in his quest to grasp the essence of their cultural and religious beliefs. Wherever travel restrictions were imposed, he communicated with Tamil intellectuals through letters. With deliberate intent, he embraced the colloquial Tamil dialect—both in conversation and writing—to effectively communicate with the local people.

Having acquainted himself with the early Tamil works of the Jesuit missionaries, Ziegenbalg began translating Christian literature into Tamil. His translation of the New Testament was published in 1714, and the translation of the Old Testament was eventually completed by his successor after his demise in 1719.

Ziegenbalg was not the first missionary to translate the New Testament into Tamil, but his rendition was the most complete and accessible of the time. He also translated Martin Luther’s Small Catechism and composed Church songs in Tamil. Palm leaf manuscript copies of his works reached several hundred people before he obtained a printing press from Halle and began publishing his materials in 1713. Though there were already a few printed Tamil books in existence, his publication is considered to have inaugurated the modern era of Tamil book-printing and printing in Indian languages as a whole.

For inclusive Tamil society

Engaging in deep discussions with Tamil intellectuals ignited Ziegenbalg’s passion for Tamil literature. By August 1708, he had read 151 books and reviewed them in his Bibliotheca Malabarica [an annotated catalogue of Tamil texts]. Over time, his personal collection of Tamil books expanded enormously. Given that his writings frequently refer to them, it appears he would have read most of them thoroughly. He translated three Tamil didactic texts: Konraiventhan, Ulakaniethi, and Niethivenba. His two important works, Ausführliche Beschreibung des Malabarischen Heidenthums and Genealogie der Malabarischen Götter, were based on his correspondence with local Tamil scholars and his survey of Tamil literature. His Grammatica Damulica was a book on Tamil Grammar.

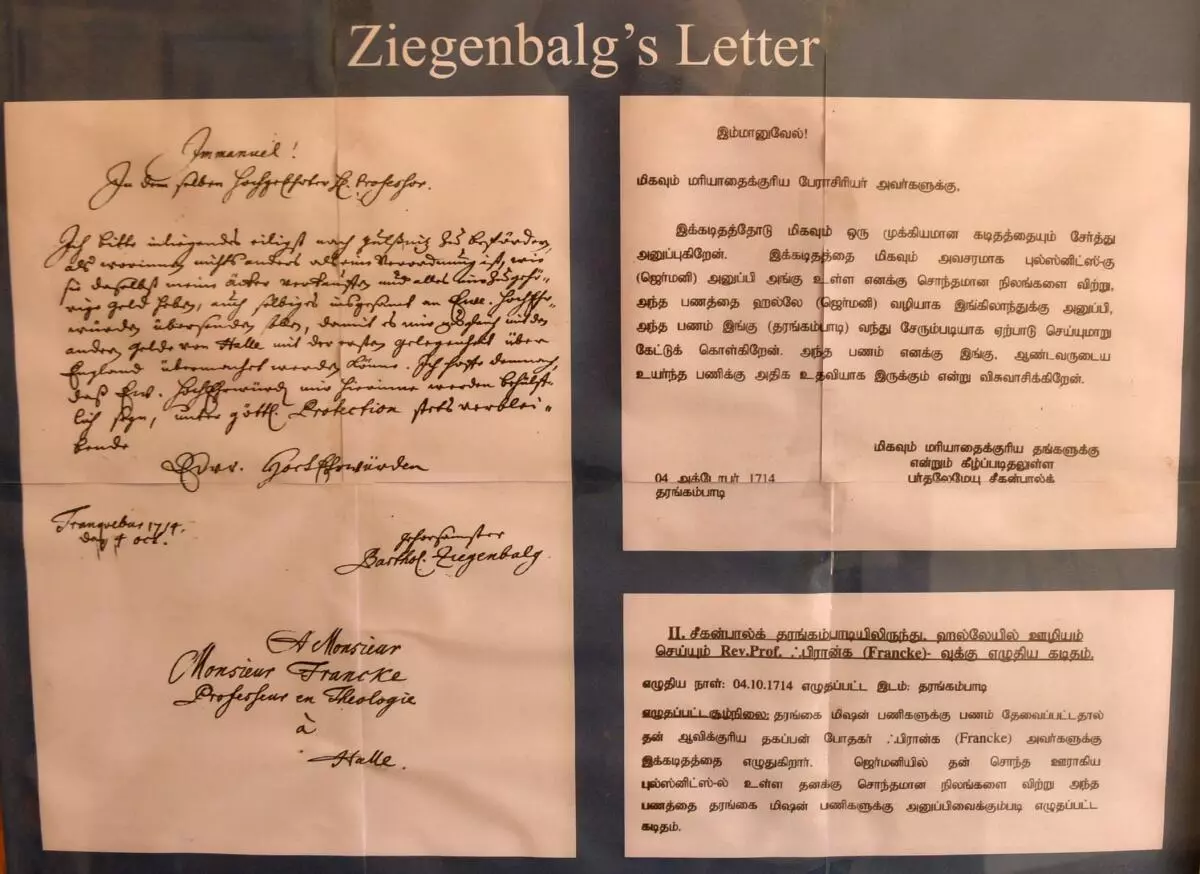

In addition to his scholarly works, he penned extensive letters to his European peers, rich with insights into Tamil culture and literature. In many cases, he simply translated the views of Tamilians, thus providing firsthand evidence to Europe. He wrote about Tamils in German, Portuguese, English, Danish, and Latin.

The copy of letters of Danish missionary Bartholomaus Ziegenbalg at Tranquebar or Tharangambadi

| Photo Credit:

Moorthy. M / The Hindu

The Tamil texts Ziegenbalg chose are interesting. He was attracted to the texts on ethical treatises,Shaiva Siddhanta, and minor literature (Sittrilakkiyam). In his listing of the most popular Tamil works, he includes the Thirukkural. These works, in general, critically engage with “Brahmanical Hinduism” and emphasise Tamil religious thoughts, such as Tamil Bhakti.

Furthermore, Ziegenbalg’s two favourite works—Kabilar Agaval and Sivavakkiyam—are known for their critical views on superstitious rituals, idol worship, and the social division of people based on Varna and caste. There were several other texts in this category that Ziegenbalg had in his preferred collection. At times, he mistakenly believed these texts might have been written by Christian authors. His own narrative style in Tamil is said to have been influenced by these minor works. Thus, Ziegenbalg’s understanding of Tamil culture deepened through these texts. He noted that the spiritual teachings of Tamilians did not contradict The Bible. Also, he criticised Europeans for their prejudice and ignorance regarding South Indians.

Ziegenbalg’s pioneering engagement with the issue of caste laid a foundational example for upcoming Protestant missionaries. Emphasising the egalitarian principles of Christianity, he advocated for his congregation to abandon caste and gender distinctions in seating arrangements in church, as well as preferences in receiving holy food. It represented a modest beginning on the daunting path that lay ahead for future Protestant missionaries.

He also ingeniously employed his mission school to cultivate a culture of social intercourse among students, transcending barriers of caste prejudice. He founded two Tamil schools, one for boys and another for girls, as well as a Portuguese school. Admitting “pariah” students to schools and ensuring students of different castes stayed and studied together posed significant challenges. He creatively employed strategies, such as dressing “pariah” students in European clothing, to mitigate apprehensions among high caste students and parents.

Also Read | Of the German who took Tamil to Europeans

By 1713, the Mission had enrolled 78 children in their schools, most of them were from suppressed castes. Though not entirely successful in his efforts, it is said that at his funeral, his converts sat together without distinctions of caste, perhaps for the first time.

The Protestant missionaries immediately following Ziegenbalg did not address the caste issue seriously and focused primarily on conversion. As a result, there was a significant caste dispute between the “pariah” and Shudra converts of the Protestant mission. This even led to the establishment of separate churches. However, Ziegenbalg’s approach to caste became a guiding principle when radical Protestant missionaries in the early decades of the nineteenth century took a firm stand against caste practices among their converts and students. In the mission school, they envisioned seeing “a Vellalan girl and a Chuckler boy, the highest and lowest, walking hand in hand as friends”.

By demonstrating the possibility of an alternative social space based on egalitarian principles, the Protestants were able to transform the previously textual dissent against caste into a practical reality. This marked a significant moment in the long history of resistance against the caste system.

Though it might seem modest, Ziegenbalg’s impact on Tamil history is profound and worthy of commemoration.

S. Gunasekaran is an Assistant Professor at the Centre for Historical Studies at Jawaharlal Nehru University.