In the summer of 1997, a gathering of 10 leading Indian novelists was “herded” into a small New York studio for a group photograph. The New Yorker was putting together a special issue to celebrate India’s golden jubilee—its 50 years of Independence from British rule—and this photograph was to be the centrepiece of the magazine’s cover story on the renaissance of Indian writing in English.

“It wasn’t an easy picture for [the photographer] to take,” said Salman Rushdie, one of the “Terrific Ten” assembled in the studio, as he described the rare moment in his memoir Joseph Anton. Bill Buford, the fiction editor of the magazine at the time, wrote in his column that the photographer had been “desperate to herd an edgy group into his frame. The results are illuminating. In the pile of pictures [the photographer took] there are variations on a theme of muted panic. There are looks of self-consciousness, of curiosity, of giddiness.”

Arundhati Roy, another member of that famous “Group Shot”, who would go on to win the Booker Prize later that year for her debut novel, The God of Small Things, said: “I chuckle when I remember that day.” In an interview to Amitava Kumar, she recalled that “everybody was being a bit spiky with everybody else. There were muted arguments, sulks and mutterings. There was brittle politeness. Everybody was a little uncomfortable, wondering what exactly it was that we had in common, what qualified us to be herded into the same photograph.”

Published in 1981, the book was awarded that year’s Booker Prize; it also won the Best of Booker twice, in 1993 and 2008.

| Photo Credit:

By Special Arrangement

The result however—the final photograph—does not betray any discomfort or friction. It is a happy picture, conveying an impression of an uneasy intimacy at best to a close observer. It manages to project (quite duplicitously) A Fine Balance, when the Midnight’s Children in the company of A Suitable Boy met The God of Small Things in Clear Light of Day, coming together in The Shadow Lines of a firangi studio, playing out their Sacred Games at A Strange and Sublime Address, thus creating a Hullabaloo in the Guava Orchard of the Indian writing and reading community of the day and thereafter.

What was it, as Roy had wondered, that these novelists had in common? Among the numerous things that define their work, one might also ask what is the connection between one’s magical realism and another’s social activism? How do Anita Desai’s and Rohinton Mistry’s quietly beautiful and delicate sentences relate to Rushdie’s boisterous literary fireworks or to Vikram Seth’s shimmering simplicity and Amitav Ghosh’s masterful hold on his obscure subjects of the Anthropocene? What is the link between Amit Chaudhuri’s arcane but exquisite literary productions and Vikram Chandra’s dexterous plots of the underworld and Roy’s resounding prayers from the marginlands? “I realised I didn’t belong in that group. Not my sort of people,” Chaudhuri told Buford afterwards. In the interview to Amitava Kumar, Roy confirmed that they had not been her sort of people either: “I don’t think anybody in that photograph felt they really belonged in the same ‘group’ as the next person.”

Published in 1993, A Suitable Boy is considered to be one of the longest novels to come out in a single volume.

| Photo Credit:

By Special Arrangement

As the “Group Shot” was being lit and taken in New York, back in India Inder Kumar Gujral had been Prime Minister for just a few months. The Congress would withdraw its support to the United Front government later that year, resulting in Gujral’s resignation and mid-term elections. The Hindu nationalists, riding high in the aftermath of the Babri Masjid demolition, had been preparing the ground and waiting in the wings. In just under a year, the BJP would ascend to power for the first time, changing India’s politics and public discourse in fundamental ways.

It was also a year of grand films that took the box office to a new high. Dil To Pagal Hai released, and its swoon-worthy songs were on everyone’s lips. Pardes, too, came out and so did Ishq, Hero No. 1, Judaai, Gupt, Koyla, Deewana Mastana, and Border. During one of the screenings of Border, at Uphaar Cinema in a posh neighbourhood of India’s capital city, a massive fire broke out, suffocating 59 people to death and injuring over a hundred others in what was one of the worst cases of criminal negligence and saddest tragedies in modern times.

Rishabh Pant the cricketer, Neeraj Chopra the Olympic Gold medallist, and Darsheel Safary the actor of Taare Zameen Par fame were born in that year, and Mother Teresa—also the subject of Christopher Hitchens’ The Missionary Position—passed away in Calcutta. Sonia Gandhi, mourning the brutal assassination of her husband, former Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi, just a few years ago, stepped out in public for the first time and agreed to campaign for the Congress in the upcoming general election, thus announcing her arrival into active politics. It was also that golden age of Tendulkar, Ganguly, and Dravid, who launched Indian cricket into the stratosphere so that wherever the team went—from Sharjah to Toronto, from Lord’s to Eden Gardens—the attending crowds, irrespective of their age, caste, language, religion, even nationality, and between such iconic commercials such as those for Pepsi, Humara Bajaj!, Washing Powder Nirma, Fevikwik, Zandu Balm, Nerolac, and Cadbury, would erupt with chants, especially for the Little Master; stadiums reverberated with the cries of Sachin! Sachin! every time he walked out to bat.

This was Roy’s debut novel, which won the Booker Prize in 1997.

| Photo Credit:

By Special Arrangement

Beyond home, in the world, the people’s princess, Lady Diana, was killed in a car crash in Paris. Steve Jobs returned to Apple just on the eve of the looming dot-com bubble. Titanic released in theatres worldwide, and the first novel in the Harry Potter series was published to unprecedented global popularity and success.

And, of course, the Republic of India celebrated its 50 years of Independence “at the stroke of the midnight hour” on August 15, 1997. It was in that moment of great political and social flux in India that most of the leading novelists from the “Group Shot” were working quietly, thinking, writing, and offering their art to the world. “For me what’s… interesting,” Roy told Amitava Kumar, “is trying to walk the path between the act of honing language to make it as private and as individual as possible, and then looking around, seeing what’s happening to millions of people and deploying that private language to speak from the heart of a crowd.”

The centre of ‘global dazzle’

After the Booker, Roy had found herself at the centre of “global dazzle” that, among other things, brought fame, applause, flowers, photographers, “journalists feigning a deep interest in [her] life, men in suits fawning over [her], and shiny hotel bathrooms with endless towels”. The powers that be—the government, the establishment, the elites, the media, the corporates—wanted her on their side. Instead, Roy declined to join the bandwagon and “seceded” to become an “independent, mobile republic”, sans any territory or flag but her arms wide open, ready to welcome any “immigrants” who wished to form the new republic with her and “help [her] design [their] flag”, much like the Jannat Guest House at the centre of her long-awaited second novel, The Ministry of Utmost Happiness. She wrote her first political essay, The End of Imagination, in response to India’s nuclear tests conducted at Pokhran in 1998 by the newly elected BJP government.

Also Read | An unbearable lightness

It is a powerful essay and a damning indictment of the new world order and the way in which India was turning. “The [nuclear] tests,” Roy wrote, “the manner in which they were announced, and the enthusiasm with which they were celebrated… ushered in a dangerous new public discourse of aggressive majoritarian nationalism—officially sanctioned now by the government itself.” Her horror at nuclear war between India and Pakistan becoming a real possibility was matched by her concerns about “what this ugly new language would do to our imaginations, to our idea of ourselves”. Indians would find that out for themselves in the coming years when the BJP, for the first time on its own, would form the government in 2014 under the leadership of Narendra Modi. But back then, in 1998, still a few years before “imagination” neared its end and on account of her stinging, prescient essay and “secession”, Roy was quickly shunned by the establishment and dropped from “the line-up of people who were chosen to personify the confident, new, market-friendly India that was finally taking its place at the high table”.

Across the seven seas from Roy, in an undisclosed corner of the world, another of India’s great novelists, Rushdie, had “seceded” into a “dark tunnel”, not by choice but as a payment of a heavy price for his imagination. He had gone into hiding after Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the Supreme Leader of Iran, issued a fatwa against him on Valentine’s Day 1989, sentencing him to death over the publication of his novel The Satanic Verses—a decree that the Nobel laureate V.S. Naipaul, perhaps jokingly, called “an extreme case of literary criticism”.

A master of irony himself, it was ironic that Rushdie was at the receiving end of international bigotry in a year that saw a historical wave of freedoms around the world, with the fall of communism and the liberation of Nelson Mandela, and the target of an act of hatred on a day of love. “It was Khomeini’s love letter to me,” Rushdie would joke about it later in his career. But back in the day, Khomeini’s rather pernicious “love letter” placed Rushdie in the eye of a dangerously ugly storm. “EXECUTE RUSHDIE ORDERS THE AYATOLLAH,” read the headlines in newspapers as the word spread like wildfire. The police acted swiftly and gathered at Rushdie’s home to offer protection. “What’s going on, Dad?” his young son, Zafar, asked him. As Rushdie describes the moment in his memoir, “his son had a look on his face that should never visit the face of a nine-year-old boy”.

In the days that followed, Rushdie would be taken to a series of secret places to stay, and it would take more than a decade for him to be able to return home. Public commentary around Rushdie and his book got more savage every day. The British novelist Martin Amis, who was a close friend, put it quite memorably (and rather shrewdly): “Salman [has] vanished into the front page.” The challenge, therefore, as Rushdie discusses in his memoir, was not just the physical danger—the possibility that he would be murdered soon, as he had feared—but also the murder of his capability to think and write in that din, having to constantly look over his shoulder, stranded far from his family and friends. He despised being on the front page. He wanted to be back on the books page as soon as he could.

Published in 1980, the book was shortlisted for that year’s Man Booker Prize.

| Photo Credit:

By Special Arrangement

He wrote and published a string of influential books through the 1990s from his various hideouts. It was the promise that he had made to Zafar many years ago that shone brightly at the end of the “dark tunnel”, calling him to sip from the ocean of the streams of stories once again. When he was on the verge of finishing The Satanic Verses, his son had said to him: “Dad, why don’t you write books I can read?” It had made Rushdie think of a line in St Judy’s Comet, a song Paul Simon wrote as a lullaby for his young son. If I can’t sing my boy to sleep, well, it makes your famous daddy look so dumb. “Good question,” Rushdie had replied to his son. “Just let me finish this book I’m working on now, and then I’ll write a book for you.” He remembered the promise, and he wrote Haroun and the Sea of Stories, his first book since the fatwa. The dedication page read:

Z embla, Zenda, Xanadu:

A ll our dream-worlds may come true.

F airy lands are fearsome too.

A s I wander far from view

R ead, and bring me home to you.

In addition to keeping his promise to his son, another talisman that “brought him home” was his own profound love for telling stories. There is a line in Joseph Conrad’s novel Nigger of the Narcissus that became Rushdie’s “motto” and to which he “clung as if to a lifeline in the long years that would follow”. The title character in Conrad’s novel, a sailor named James Wait, stricken down by tuberculosis on a long sea voyage, was asked by a fellow sailor why he came aboard knowing, as he must have known, that he was unwell. “I must live until I die, mustn’t I?” Wait replied. In Rushdie’s present circumstances, “the sentence’s power felt like a command”. He told himself: “You must live until you die.”

Took on another enemy

Not too long before the “Group Shot” happened, Rushdie had written and published another novel, The Moor’s Last Sigh, that, among other things of beauty and top-notch storytelling, took on yet another enemy of free thought and expression in the form of Hindu bigots this time as Hindu majoritarianism in India ran amok after the Babri Masjid demolition. Different gang, same problem. And between Khomeini and Rushdie, between the sword and the pen, it has to be said that Rushdie’s pen has continued to flow. His life though, more vulnerable than his words, took another dangerous turn when he was attacked and stabbed more than 15 times in a single incident in 2022. In spite of the unimaginable trauma and even losing an eye, he lived to tell the tale.

During a reading event at the New York Public Library on August 19, 2022, participants express their solidarity with Salman Rushdie days after he was brutally attacked when he was about to give a lecture in the city.

| Photo Credit:

YUKI IWAMURA/AP/PTI

Rushdie and Roy are just two ways to look at the photograph to try to understand what this gathering stood for and the role each of these novelists played in the development and blooming of Indian writing in English. One could look at the photograph from various other points of view, from Seth’s deployment of subtle, ironic prose to mine simple, essential, anxiously relatable, and, therefore, radical truths about a complicated society, to Anita Desai’s self-assured language and talent to take just a strand of hair from the head of a goddess and turn it under the light to evoke a bygone era, a lost culture, and the values of family and friends.

Also Read | Knife by Salman Rushdie: Chronicle of a death foretold—and foiled

The “Group Shot”, in addition to being a sentimental one for many who follow and engage with Indian writing in English, is also a reminder of the last gathering of such writers who did not succumb to political propaganda, indulge in expedient social and moral grandstanding, or use their celebrity for their own benefit. Amid the amazing riot of differences between them, their writings, and their politics, what makes them a part of a single whole and qualifies them to be “herded into the same photograph” is their fierce artistic independence and nonconformity. In addition to entertaining and telling a story, they have empowered literature as a site of not just pleasure but also of protest.

They have taken English—that imperial, colonial inheritance—and in a very Indian way, grabbed it, assimilated it, recast it, and honed it to tell their stories, making it into yet another Indian language. While Rushdie, the leader of the pack in this department, has protested against the Official History and Official Memory through his stories and stood for multiplicity of remembrances, Roy has exposed “the great project of unseeing” the injustices and ventured into forests, across rivers and dams, down through contested valleys to tell us of lives at the borders of our pop culture, gated townships, and growling cities.

Arundhati Roy and the Narmada Bachao Andolan leader Medha Patkar with other activists at a demonstration in New Delhi on May 9, 2006. Roy has exposed “the great project of unseeing” the injustices and ventured into forests, across rivers and dams, down through contested valleys to tell us of lives at the borders of our cities.

| Photo Credit:

R.V. Moorthy

Similarly, Ghosh has not conformed to the subjects of the “mainstream”. He has questioned the Official Narrative and ignored national boundaries in order to include and privilege local people’s histories, facts, lore, locations—across the Indian Ocean. And by utilising the simple metaphor of Indian matchmaking and language of irony, Seth, ever so in love and in favour of love, has punctured holes in the facade of a formidably complex society and refused to conform to its customs and conventions.

They are the writers, the artists, the storytellers who did not sell their souls.

Together, many of the novelists in the “Group Shot”, and many others who are not in that photograph, helped induce a milieu in which Indian writing in English has mushroomed in the years since, albeit not often of the same quality and integrity. From Fifty Shades of Chetan Bhagat, which are marketed and sold crazily akin to fast moving consumer goods, on one end of the literary spectrum, to most of the MFA-novel—“which”, in the words of Roy, “can often be a beautifully confected product”—on the other end, the Indian English novel’s second, or perhaps the third, coming is awaited. Both these ends of the literary spectrum are for the here and now, and somewhere from between these ends of mundane entertainment that barely scratch the surface of our inner lives, on the one hand, and the self-righteous, superior-than-thou, artificial creations, on the other, will emerge the next best of Indian writing in English.

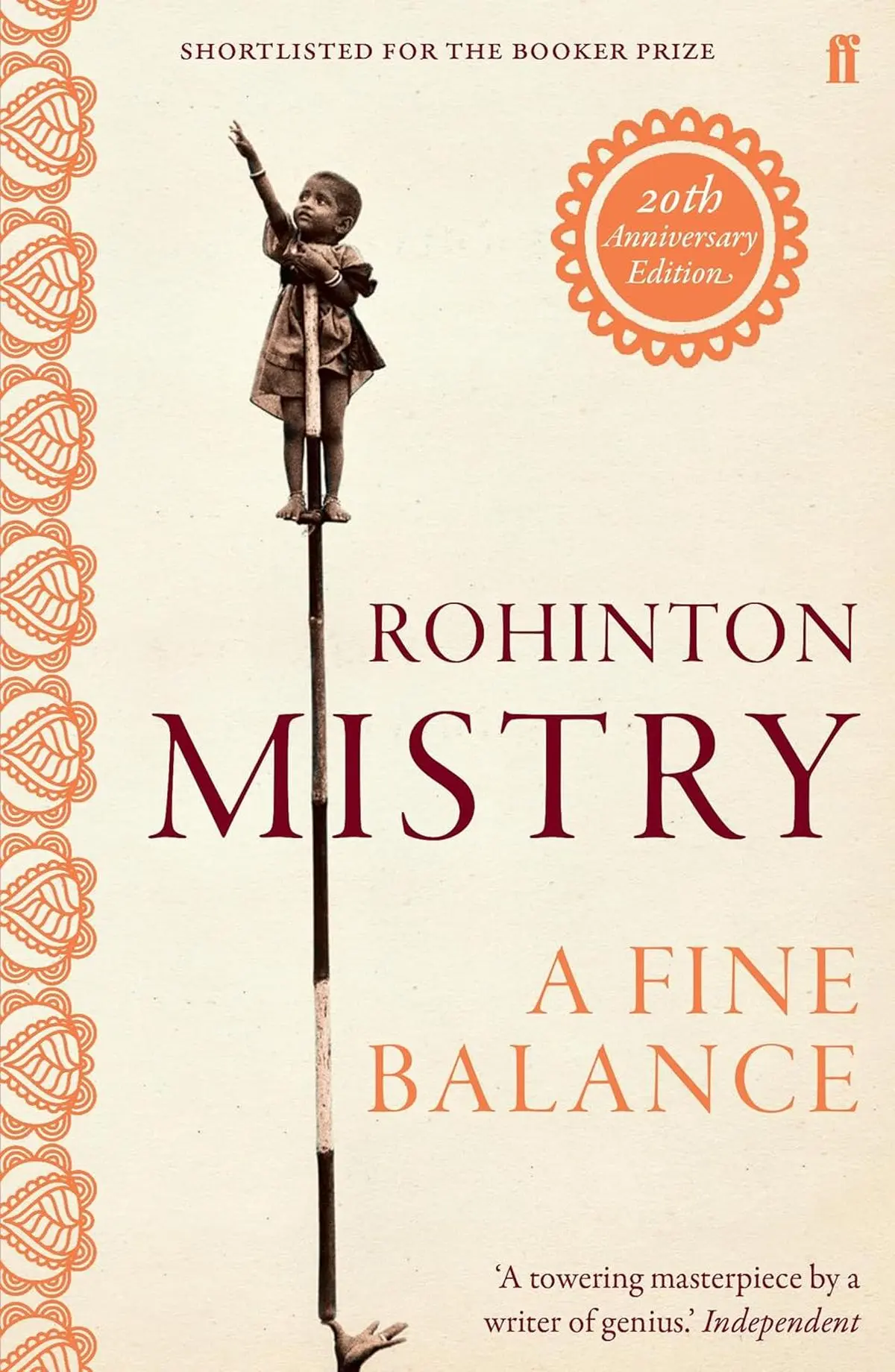

Published in 1995, this is Mistry’s second novel; it was shortlisted for the Booker Prize the following year.

| Photo Credit:

By Special Arrangement

That is not to say there are not any fine and exciting Indian English novelists working and writing in our times. There are, in fact, many: Anuradha Roy, Rana Dasgupta, Aatish Taseer, Jeet Thayil, Nilanjana Roy, Janice Pariat, Shubhangi Swarup, Annie Zaidi, Roshan Ali, Chandrahas Choudhury, Tejaswini Apte-Rahm, Saharu Nusaiba Kannanari, and others. But, as the best of novels are those that last and transcend at least a generation or two of readership, the jury is still out on which novelists after the phenomenon of Rushdie-Roy-Seth-Ghosh and Co. would have taken and will take the Indian English novel to its next moment of liberation, on to its next pedestal of greatness. (Disclosure: I was the publicist assigned at HarperCollins India for Pariat’s novel Everything the Light Touches and am presently a marketing consultant for a literary agency that represents Kannanari.)

Also Read | Reading Arundhati Roy politically

For now, there is a palpable loss of literary influence in India. Rushdie, looking around at the literary scene, noted in his talk at Emory University: “I have a slightly depressing sense that writers are not particularly listened to in India any more. There are figures who have some stature like Arundhati, like Vikram Seth, and some journalists who have been very prominent for a long time, and it’s good to see those people use that platform in order to say things that need to be said. I just worry that not many people are listening any more.”

Loss of literary influence

This loss of literary influence is not only a result of the quality of most of the recent Indian writing in English. It is also an insidious consequence of a variety of other factors, including the depth and range of the world view of most publishers and editors; the gimmicky, one-track juggernauts of marketing and sales apparatus that try to make Amish Tripathi sound like J.R.R. Tolkien; the creamy froth of well-manicured, well-connected authors Desperately Seeking Fame; the literary elites who know each other and their cousins, moving around in the same fashionable, incestuous literary circuits, acting as immigration inspectors to anyone trying to break out with their first draft; and, finally, the increasing lack of discerning readers who, at the end of the day, are also bombarded with stories from other media, art forms, modes of entertainment, and that new prince of “content” in town, namely, Netflix (and its equally rich next of kin).

These are the heavy chains that Indian writing in English still needs to break and liberate itself from. Starting out from the generation of R.K. Narayan, Mulk Raj Anand, Raja Rao, G.V. Desani, and others, down to the next generation, some notable members of which featured in the “Group Shot”, the best of novelists have always removed the most pressing shackles of their time and taken the art of storytelling forward. When India celebrates its 100 years of Independence—its I-don’t-know-which-gem-stone jubilee—may there be another “Group Shot”. May there be a new gathering of beloved novelists from a myriad other languages and experiences of India (for Indian writing in English is just a tiny part of Indian literature and reaches a tiny percentage of India’s population), and hopefully this time splashed across an Indian newspaper or magazine, telling the tale of those storytellers who touched their readers to the core and maybe even offered a new vision to their societies, and took the ancient art of telling a story and delighting a thousand and one hearts into a new age.

May the “Group Shot” be just the last Gathering… and not the Last gathering!

Shivendra Singh is a writer from Lucknow.