The recently concluded Bengal Biennale has been remarkably successful in its very first edition. Organised in tandem in Santiniketan and Kolkata, it ran from November 29 to December 22, 2024, in Santiniketan, and from December 6, 2024, to January 5, 2025, in Kolkata. Since the required infrastructure for holding such a grand art event is nearly non-existent in West Bengal, the initial scepticism about a Bengal Biennale was perhaps justified. There were a few glitches, of course, but it managed to leave its mark, both in terms of the displays and the viewers’ response. Commenting on its success, Bose Krishnamachari, co-founder and president of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale, said: “The first edition of the Bengal Biennale beautifully captured the spirit of community and collective engagement, especially through the inspiring works of young artists.”

The odds were against the organisers. In Bengal, successive governments have failed to create designated spaces to display Bengal’s contribution as the birthplace of Indian modernism and its brilliant achievements in the area of visual arts. The Gurusaday Museum in the outskirts of Kolkata had a priceless collection of folk and tribal arts. Inaugurated in 1961, it shut down in 2017 and folded up during the pandemic. While funding for serious art projects and museums is scarce, crores are squandered on hideous “public art” displays. The house of Lady Ranu Mookerjee, once Bengal’s culture czarina, has been turned into yet another banquet hall. The artist Shanu Lahiri’s sculpture installed at a prominent roundabout disappeared overnight in November 2014 without any explanation.

There was a furore recently when it came to light that the Jaipuri murals on the staircase and entrance of Kolkata’s Government College of Art and Craft, already tainted by the fake Rabindranath Tagore paintings scandal of 2011, had been whitewashed. The murals dated back to the time when Abanindranath Tagore was the Vice Principal of the institution, which has produced some of India’s leading artists down the decades. The overall decline has not spared even Rabindranath Tagore’s Visva Bharati, which is now synonymous with dirty politics. The present environment in Bengal is certainly not conducive to a reflowering of art, craft, and culture. The dazzling lights that perennially festoon roads, flyovers, and bridges cannot conceal the battered core of Kolkata.

Beyond the gloom and doom of Kolkata

Given the dismal scenario, it must have taken a lot of courage on the part of the organisers—the entrepreneur couple Malavika and Jeet Banerjee and the curator and director Siddharth Sivakumar—to take up the challenge of choreographing an art event with an impressive line-up of artists from within and outside West Bengal, some of them of international standing. Malavika, who has been organising the Kolkata Literary Meet since 2012, said: “Ever since Jeet visited the Shanghai Biennale in 2016, we have been contemplating the possibilities of holding such an event in Bengal but we didn’t have the bandwidth at that time. The 2023-2024 period proved to be a good time for it. We had thought of two centres. We started with Santiniketan as it has so many art spaces.

Also Read | Art of resistance: Venice Biennale, 2024

“As to Kolkata, we had to understand the strength of the city. It has some amazing colonial buildings. In June 2024, it was decided that the Bengal Biennale would be held in both centres. Everyone was enthusiastic and supportive, both the art fraternity and the gallerists. Partners came forth only in September, and sponsorship offers were coming in even two weeks before it started.

“Museums attract a lot of people, and art has to be public-facing, moving out of cloistered galleries. It must involve craftspeople and all kinds of things. We would like to leave behind the typical doom and gloom associated with Kolkata.”

Highlights

- The inaugural edition of the Bengal Biennale was held in tandem in Santiniketan and Kolkata.

- The humongous Bengal Biennale meandered along roads less travelled in such art events, in keeping with its theme of “Anka Banka: Through Cross-Currents”.

- It was a remarkable medley of artists, pedagogues, as well as of craftspeople and professionals from disciplines such as textile, photography, music, and theatre.

Sivakumar said: “The idea had been on my mind for years but always seemed too ambitious to pursue. Then, in February 2024, a chance encounter with Jeet at a party changed everything. We discussed organising a smaller art event in Santiniketan, centred on exhibitions. Interestingly, when I first met Jeet in 2022, he had talked about creating a biennale. That larger vision lingered in the background as we began working on the Santiniketan project. By June, logistical challenges made it clear that we needed to expand beyond Santiniketan. Kolkata, with its infrastructure and cultural significance, became the obvious choice. With the experience of Malavika and Jeet in the cultural and sports worlds [Gameplan, set up by the duo in 1998, is a corporate branding agency working primarily in the fields of sports and literature], the transition felt seamless. What began as a localised initiative evolved into a larger collaboration, connecting Santiniketan’s artistic spirit with Kolkata’s cultural vibrancy.”

The installation “I am Ol Chiki” with Mithu Sen (in red sari).

| Photo Credit:

Bengal Biennale

The eminent art historian R. Siva Kumar, who was on the panel of advisers, said: “I gave them my moral support and chipped in when they asked for some special help, without interfering in the overall planning or execution. I know that some of the other advisers have suggested a greater focus on Asia in forthcoming editions.”

Remarkable collaboration

With the will to create the exhibition in place, hidebound government institutions fell into line. About 80 works from its collection of 110 paintings by Rabindranath Tagore were on display at Kala Bhavana’s Nandan Museum in Santiniketan from November 25 to December 19. In Kolkata, an immense hall in the Indian Museum resonated with music and joy as viewers took in the stunning black-and-white frames by the celebrated photographer Dayanita Singh. Titled “Museum of Tanpura” (December 6 to January 6), the series was on display for the first time. Singh had approached Malavika with a proposal to exhibit her work at the bienniale. Arijit Dutta Choudhury, Director General of the National Council of Science Museums, with additional charge of the Indian Museum, agreed to lend the space. The Alipore Museum, a heritage structure that was once the Alipore Central Jail, featured as a venue too, hosting five exhibitions.

Musical lens

Images from the exclusive world of Hindustani classical music.

Dayanita Singh’s exhibition of black-and-white photographs titled “Museum of Tanpura” was an open sesame to the very private world of great Indian classical musicians. During an interaction with viewers on December 6 at the Indian Museum, Singh went back to 1981, when she was a student at the National Institute of Design. In a “life-changing moment” in 1981, she had met the tabla maestro Zakir Hussain, her “guru”, who started mentoring her in a “strict fashion”. He persuaded her “to find something that will stay with you for the rest of your life”. “My talim was in how to be invisible,” Singh said. Hussain instructed her “to make the camera silent” and “not to keep changing lenses, as it obstructs”. The black-and-white medium became her “mother tongue”.

Hussain facilitated Singh’s entry into the exclusive domain of Indian classical music, enabling her to photograph legends like Mallikarjun Mansur, V.G. Jog, Gangubai Hangal, Alla Rakha Khan, Bhimsen Joshi, Kishori Amonkar, and a young Rashid Khan during riyaz. The tanpura’s drone being the melodic foundation of Indian classical music, the exhibition was a celebration of this elegant musical instrument.

The invaluable image archive also recorded the passage of time. In one frame, Girija Devi was dark-haired. In another, she was grey. The recent passing away of Zakir Hussain and Rashid Khan gave the photographs an added poignancy.

Samarendra Kumar, Secretary and Curator (in charge), Victoria Memorial, wanted to show the paintings of the three Tagore siblings: Gaganendranath, Abanindranath, and Sunayani Debi. In paintings whose limpid colours glowed softly like gems, Abanindranath retold the enchanting tales of The Arabian Nights, relocating them to the familiar surroundings of Kolkata’s Chitpur, where the Tagores lived, and leavening everything with his self-deprecating wit. Gaganendranath’s shadowy, veiled women within Cubism-haunted interiors reminded one of Swinburne’s “shape and shadow of mystic things” (from the poem “Cleopatra”). This segment of the Bengal Biennale was titled “Between Home & the World: Arabian Nights, Cubist Expressions, and Feminine Interiors of Jorasanko” (December 7-January 5).

Dayanita Singh at the exhibition.

| Photo Credit:

Bengal Biennale

The only art event in Kolkata from the past that can be compared to the Bengal Bienniale is the Calcutta Metropolitan Festival of Art 1997, organised entirely by Bengali artists on the 50th year of India’s Independence. This exhibition of photographs, catalogues, posters, and archival documents held at the Jogen Chowdhury Centre for Arts from December 16 to 31, 1997, was a pronouncedly vernacular event. The artist Ganesh Haloi had moved mountains to display 200 masterpieces of Bengal’s art at the Calcutta Information Centre. The show had attracted intellectuals and art historians from India and abroad.

The humongous Bengal Biennale meandered along roads less travelled, in keeping with its theme of “Anka Banka: Through Cross-Currents”. With 100 artists participating, it reached out to all. Dialogues and symposiums featured artists, pedagogues, as well as craftspeople and professionals from disciplines such as textile, photography, music, and theatre. Besides the big solo shows, there were workshops, studio visits, and theatre, music, and dance performances. This rich cross-pollination of ideas can potentially give the dormant art scene of Bengal and east India a significant boost in the near future. Of course, the entire exhibition would have tanked if individual artists had not worked hard to mount their shows. Their dedication and enthusiasm were evident in all the segments of the Bengal Biennale.

Of the two centres, Santiniketan was, by far, the more innovative and exciting as it involved younger artists. Visitors who braved bone-rattling electric rickshaw rides along Santiniketan’s pitted roads were taken by surprise by the wonderful venues, some tucked away in lanes.

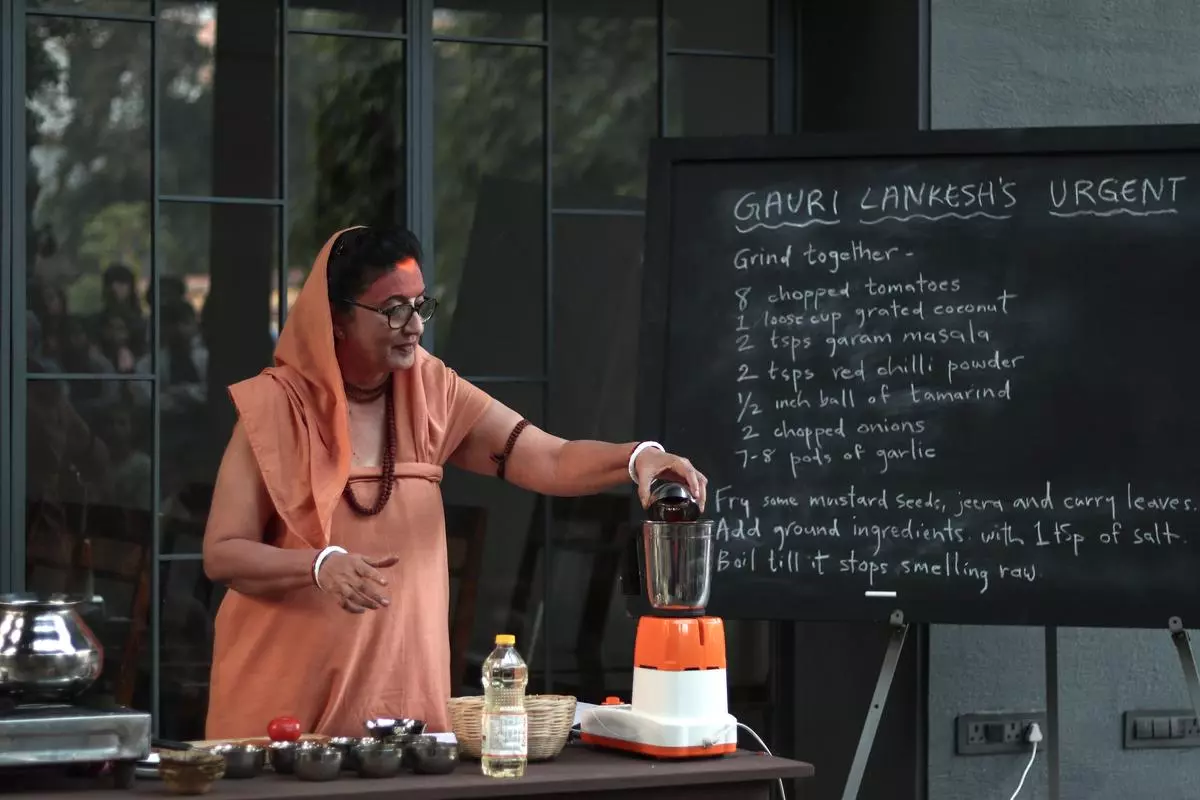

Pushpamala at the performance of “Gauri Lankesh’s Urgent Saaru”.

| Photo Credit:

Bengal Biennale

Santiniketan was originally the home of the Santhal tribe. With children being taught mostly in Bengali in schools these days, they have lost touch with the Santhali script, Ol Chiki. The conceptual artist Mithu Sen symbolically gave back the Santhali inhabitants of Pearson Palli (a locality in Santiniketan) their script by emblazoning enlarged versions of select letters from the Ol Chiki script on the restored walls of four huts. The letters brightened up the mud walls. Sanyasi Lohar, an educator, Bodi Baksi, a Santhali language activist, and seven girls and five women from the village collaborated with Sen on this invigorating project titled “I am Ol Chiki” (November 4-November 28).

Superb installations

A three-storeyed building that is home to a group of artists had been literally turned into a colourful, polygonal “Kanthar Ghar” (House of Kantha, or Quilt), with the entire structure draped with kanthas. Nearly 100 women from Birbhum—all homemakers who supplement their family income by making these layered quilts with discarded saris in their spare time—participated in this project initiated by GABAA, an artist-led centre in Santiniketan. Using seven to eight varieties of stitches, the women embroidered their life stories on the old saris, turning the kanthas into archives.

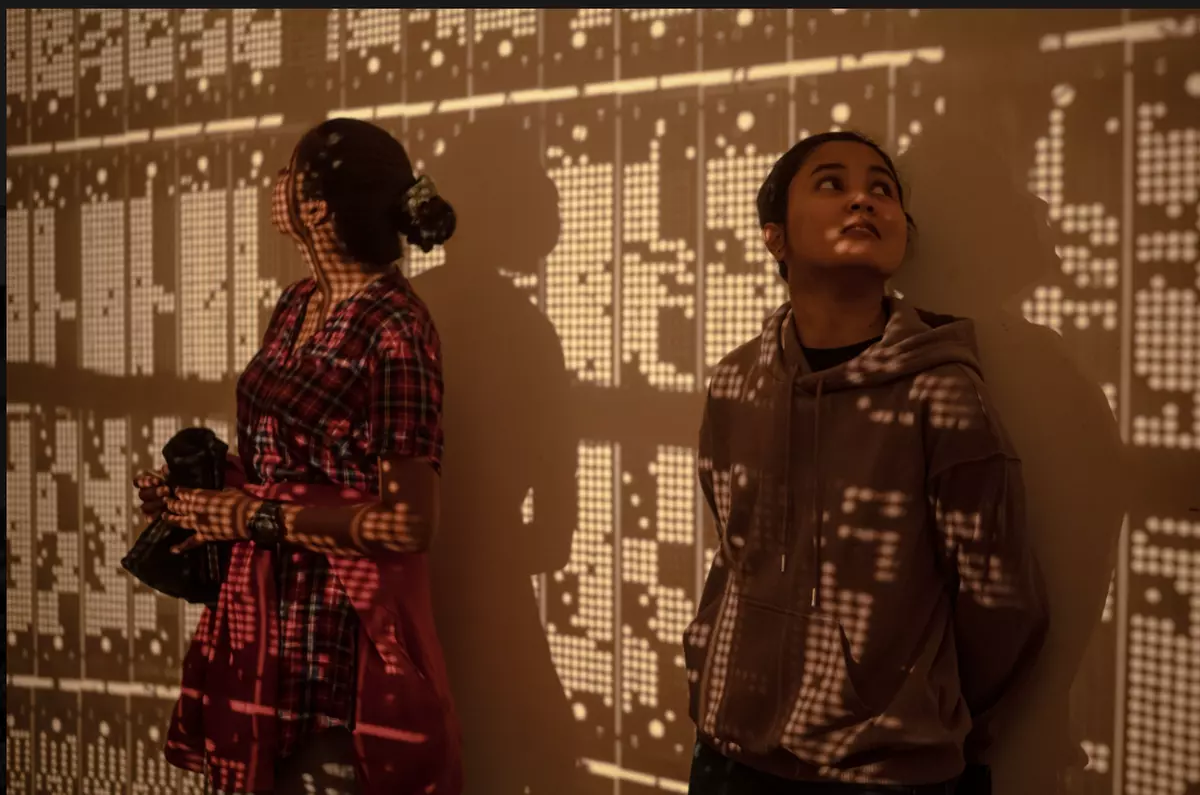

The walls of moving shadow and light around Archana Hande’s installation, “Weaving Light”, could easily had been mistaken for an intricately worked jali. In actuality, the installation was made of punched cards used in the Jacquard loom, which simplified the process of textile production in the 19th century and rendered weavers redundant. Hande used rejected punched cards that are analogue but, at the same time, are predecessors of computer technology. The digital timer light went round in a loop, casting the shadow of the punched cards on the walls so that it seemed that they were going round in circles. The moving shadows could create a sense of anxiety among viewers, reflecting the mill workers’ concern.

Archana Hande’s installation “Weaving Light” from the section “Imprint: Chhap”.

| Photo Credit:

Bengal Biennale

The fact that Hande used the studio of the sculptors and printmakers Somnath and Reba Hore for her installation was in keeping with the leftist concerns of the famous artists. Hande had invited the artist Samit Das, known for his work on the coexistence of ideologies in Santiniketan, as a collaborator in the project, which ran from November 29 to December 22.

The black-and-white photographs of Dhiraj Rabha (29) took viewers to the rehabilitation camp for former activists of the United Liberation Front of Asom in Goalpara, Assam. It is where his parents, Kaushalya and Dhananjay Rabha, live and where he grew up with his two sisters. Along with other activists, his father, once a fugitive, laid down arms in 1999. Dhiraj, once a student of Kala Bhavana who makes drawings with charcoal, had taken these photographs with his mobile phone to record daily life in the camps. Dhiraj displayed his photographs in Potthead Studio, Santiniketan, in a reconstructed ongari—a bamboo structure that preserves items above the fire in the kitchen in layers of smoke. Titled “Ongari” (November 29 to December 22), the exhibition alluded to the tribal kitchen where food is cooked and stories are told. In his Dhiraj’s presentation, the ongari was a metaphor of his desire to safeguard the stories of his family.

Sudhir Patwardhan, “Accident on May Day”, 1981, oil on canvas.

| Photo Credit:

Prakash Rao

Sudhir Patwardhan displayed a powerful body of his works, including drawings, at the Santiniketan Society of Visual Art and Design in the segment titled “Fragments of Belonging: The Paintings of Sudhir Patwardhan”. The Mumbai in his paintings is a roiling metropolis that can barely cope with the ever-increasing pressure of its proliferating populace and where violence is an everyday affair. Weighed down and torn asunder by mega building projects and the underground railway construction work, the middle and working classes seem to have lost their humanity. But not for Patwardhan, who gives every figure in the crowd an individual character.

Nikhil Chopra emerged from wraps of white cloth that he used later as his canvas during his six-hour-long live performance, “Land Becoming Water”, in the GABAA space, on November 30. He partially chewed a burnt wood stick and spat it out. Using his face and body to express his ecological concerns, he traced out the beleaguered landscape of Santiniketan with the black stick.

The artist Pushpamala happened to be the friend and neighbour of the journalist Gauri Lankesh, who was assassinated in 2017 for her political views. On December 13, Pushpamala in the garb of Abanindranath Tagore’s austere, four-armed Bharat Mata—not the Hindutva icon with a crowned head—cooked a quick curry, whose recipe Lankesh’s mother had once shared with her (“Gauri Lankesh’s Urgent Saaru”). The artist became goddess Annapurna as the “prasad” was distributed. The blood-red tomato chutney alluded to Christ’s sacrifice as well. The performance was also a dig at MasterChef TV shows that captivate millions.

From Nikhil Chopra’s performance, “When Land Becomes Water”.

| Photo Credit:

Bengal Biennale

Expertly curated by Tapati Guha-Thakurta and Mrinalini Vasudevan, the archival exhibition “A Star Named Arundhati” at Arthshila, Santiniketan, told the untold story of the Bengali film actress, producer and director of the same name.

While most of the Kolkata venues were concentrated in the south of the city, one had to travel miles to reach Arts Acre in New Town, a township in the city’s northern outskirts. The space hosted six exhibitions, of which “Beyond the Frame: Shanu Lahiri’s Art of Transformation” made the long trek worth it. Artist and teacher, wife and mother, Shanu Lahiri (1928-2013) was one of Kolkata’s indefatigable public artists who made the entire city her canvas. She worked with all classes of people in her effort to beautify the city. Her work was unappreciated during her lifetime, but her indomitable spirit came alive in the exhibition featuring a 72 ft-long made scroll by her.

Spirit of experimentation

Jayashree Chakravarty’s display, “Anka-Banka Jomi/Winding Terrain” at Arts Acre may have had the dimensions of a leviathan, but revealed a world of fascinating and intricate details on close inspection. The 55 ft-long scroll hanging mid air, swinging gently like a living thing, casting dramatic shadows on the concrete walls within which it was confined, was a perfect metaphor for the onslaught of urbanisation on nature, and how resilient nature inevitably reclaims its lost domain.

Also Read | Art and the political imagination

At Alipore Museum, the colonial jail where freedom fighters, including Jawaharlal Nehru, were imprisoned, Sheela Gowda’s installation “Interrogation Room” raised questions—with a prickly sense of humour—about the meaning of freedom in our troubled times.

The Mumbai-based artist Shakuntala Kulkarni, who was a student in Kala Bhavana’s graphics department almost 40 years ago, visited both Kolkata and Santiniketan and talked excitedly about the “compactness” of the Bengal Biennale compared with the sprawl of the Venice Biennale. The presence of young artists and experimentation was stimulating throughout. The most popular selfie point proved to be outside Victoria Memorial’s south gate, where Paresh Maity had installed a humongous jackfruit.

As the Bengal Bienniale drew to a close on January 5 with Amitav Ghosh speaking on “The Art of the Opium Trade” and a flute recital by Rakesh Chaurasia, Malavika said: “The plan is to take a step back over the next couple of weeks and then start making plans for November 2026 from February. In my head, we are looking ahead to Friday, November 27, 2026 already! As for the programme, we will follow the two-centre plan and learn from mistakes.” Who will be the next curator? “No clue!” said Malavika. “Siddharth will decide on that,” she added.

Soumitra Das is a freelance journalist based in Kolkata.