Frontline’s Books and Culture pages have featured a dazzling array of authors and artists over the years. A guided tour.

1984: R.K. Narayan

The legendary writer has been associated with Frontline since its inception. The second issue of the magazine in 1984 introduced his column “Table Talk”. An excerpt from its first instalment (“The Nobel Prize and all that”, December 14, 1984).

The Nobel-Award watchers seem to be self-appointed busybodies. Alfred Nobel the dynamitician might not have possessed deep or wide conceptions of science or literature or other subjects, but created an endowment because he liked to do so.

Alfred Nobel might not have been aware of the subtler aspects of language or literature, but seems to have just specified, rather naively, that a work should promote “idealism”. If his condition is strictly followed, the only literature qualifying for the Nobel Prize would have been “Self-Help” by Samuel Smiles or “How to Win Friends and Influence People” or “Baby Care” by Dr. Spock. But judges have stretched the notion of idealism so that Hemingway and Neruda, Patrick White, Canetti, and another and another could be chosen for the award.”

Read the article here.

Photo Credits: The Hindu Archives

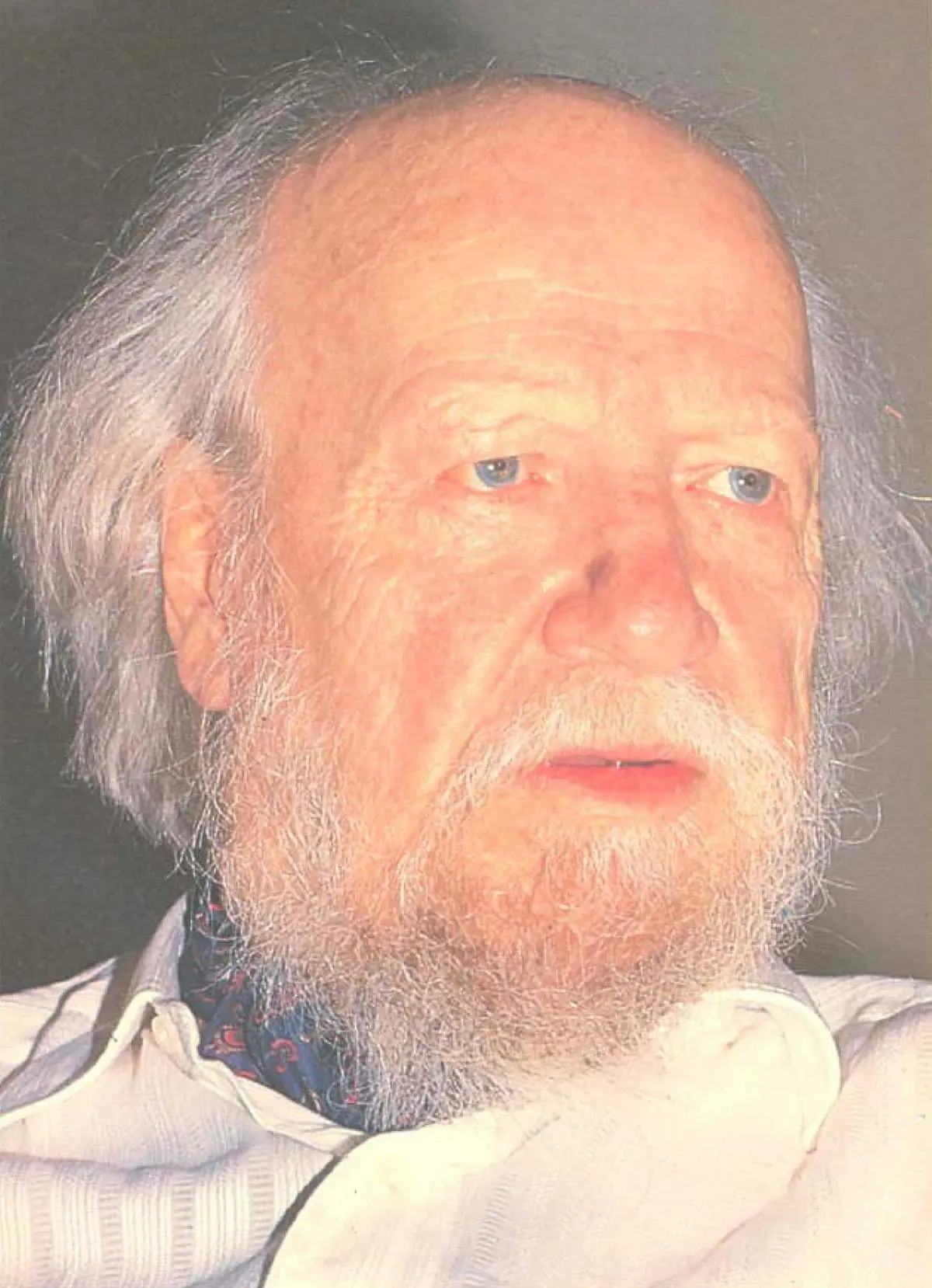

1987: William Golding

The Nobel Prize–winning novelist visited India in 1987 on a British Council invitation. An excerpt from an interview with Nirmala Lakshman, the present Chairperson of The Hindu Group (“Against straitjackets—A conversation with William Golding”, March 20, 1987).

“It’s possible,” he says, “to remain constantly astonished at everything.” He marvels at India, is absorbed, amazed and distressed, and identifies the common human spirit that abounds everywhere.

This same wonder works against the construction of formulae and the solidifying of images and revolts against a prescribed awareness. Golding experiences, as he says, “a slow burn”, or a rage against this kind of stultification. One of the evils of this century, he feels, is the “mummification” of figures like Marx, Freud and Darwin; and indeed the tendency constantly to create totemistic images by which most people seem to live out their lives.

Is there not such an image-building around him? How does he escape from the procession? “I step out all the time and stick my tongue out at myself,” he responds with a smile.

Read the full interview here.

Photo Credits: The Hindu Archives

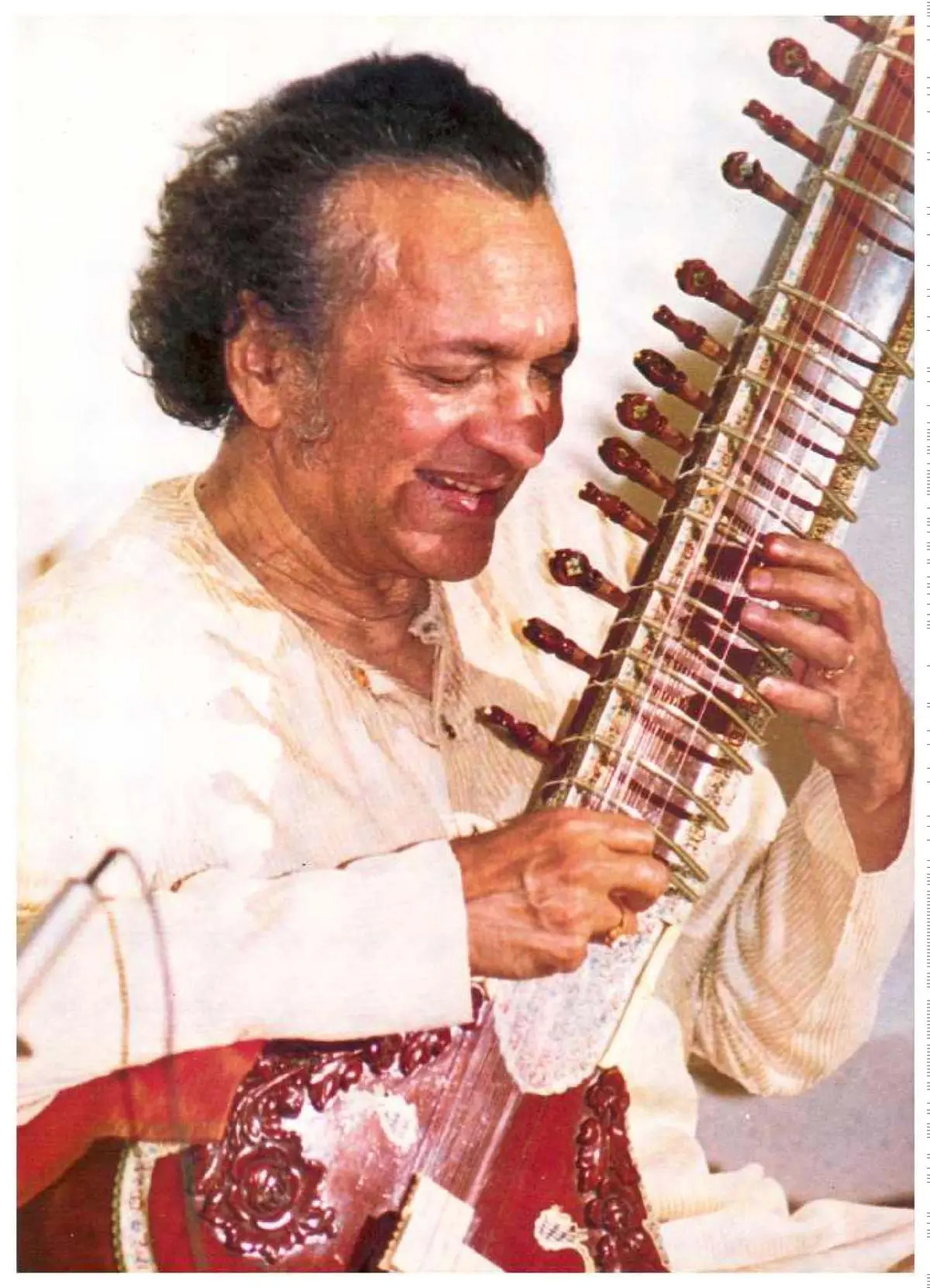

1989: Ravi Shankar

In 1989, the sitar maestro completed 50 years of concert performance. In an interview with Susheela Mishra in Lucknow (“For the soul in music”, April 14, 1989), he spoke at length about his delights and disappointments.

“I no longer find that old Benares there. All that I find is the predominance of goonda elements. Everyone wants to knife someone—that sort of mentality. I was looking for a different Benares. In fact I want to travel a little more in U.P. which happens to be my foster home. Although I happen to be a Bengali, I was brought up in U.P. Allahabad used to have so much music and culture in the past. I started my performing career with a public concert in the Allahabad Conference in 1939. This is my 50th year of concertising. Then I remember Lucknow where I used to come with Baba [Ustad Allauddin Khan] often to perform and broadcast. I used to meet so many great musicians there in the Music College, at All India Radio. Comparing with the thousands-strong audiences that I had during my last two performances here more than 10 or 12 years ago, look at the audiences today. It pains me. Where is U.P. going? What has happened to this city that could boast of Nawab Wajid Ali Shah, Kathak, and that great college headed by Pandit Bhatkhande? What are they doing now? What do they produce?”

Read the full interview here.

Photo Credits: By Special Arrangement

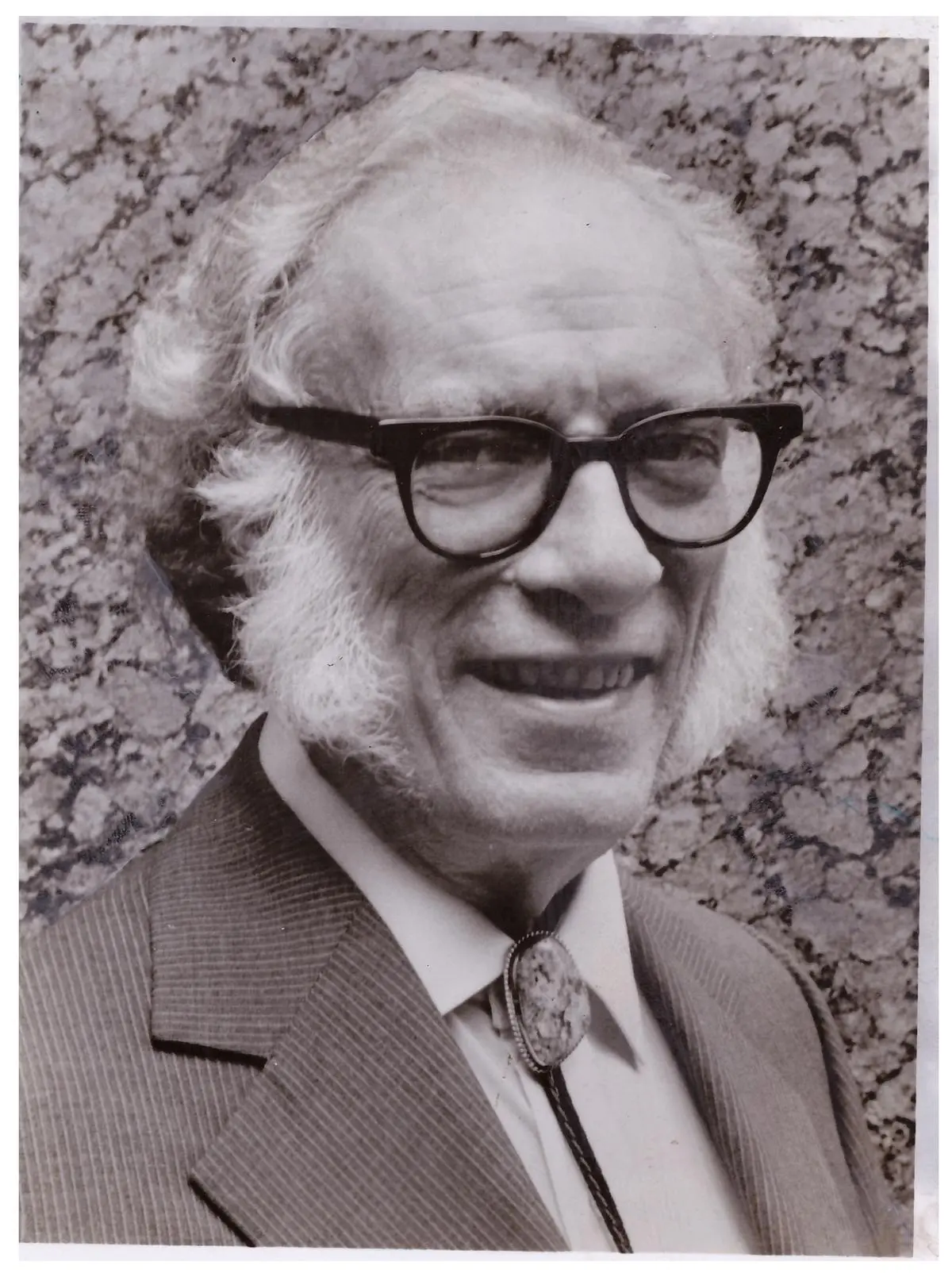

1990: Isaac Asimov

In an interview with Gowri Ramnarayan (“Of science and fiction”, September 14, 1990) at Doubleday Publishing House in New York’s Fifth Avenue, the science fiction writer talked about his books, robots, and fielding criticism with humour.

Q: The tales of mechanical monsters by your predecessors traded on the Frankenstein complex of viewing robots with apprehension and fear. But you made your robots not only perfectly safe, but much more likeable than your human characters.

A: I certainly liked them more. In a way I suppose it is because you cannot live in this world without becoming disillusioned by the people. Especially if you grew up in the Thirties with the Depression, the danger of war, Hitler’s madness…. It was difficult to think of human beings as wonderful. Of course, from the start I always described my robots in a benevolent way. They were never dangerous. They were always working for humanity. In fact the “Three Laws of Robotics” that I worked out in 1942 are golden rules which should be followed by saintly human beings!

Read the full interview here.

Photo Credits: Alex Gotfryd

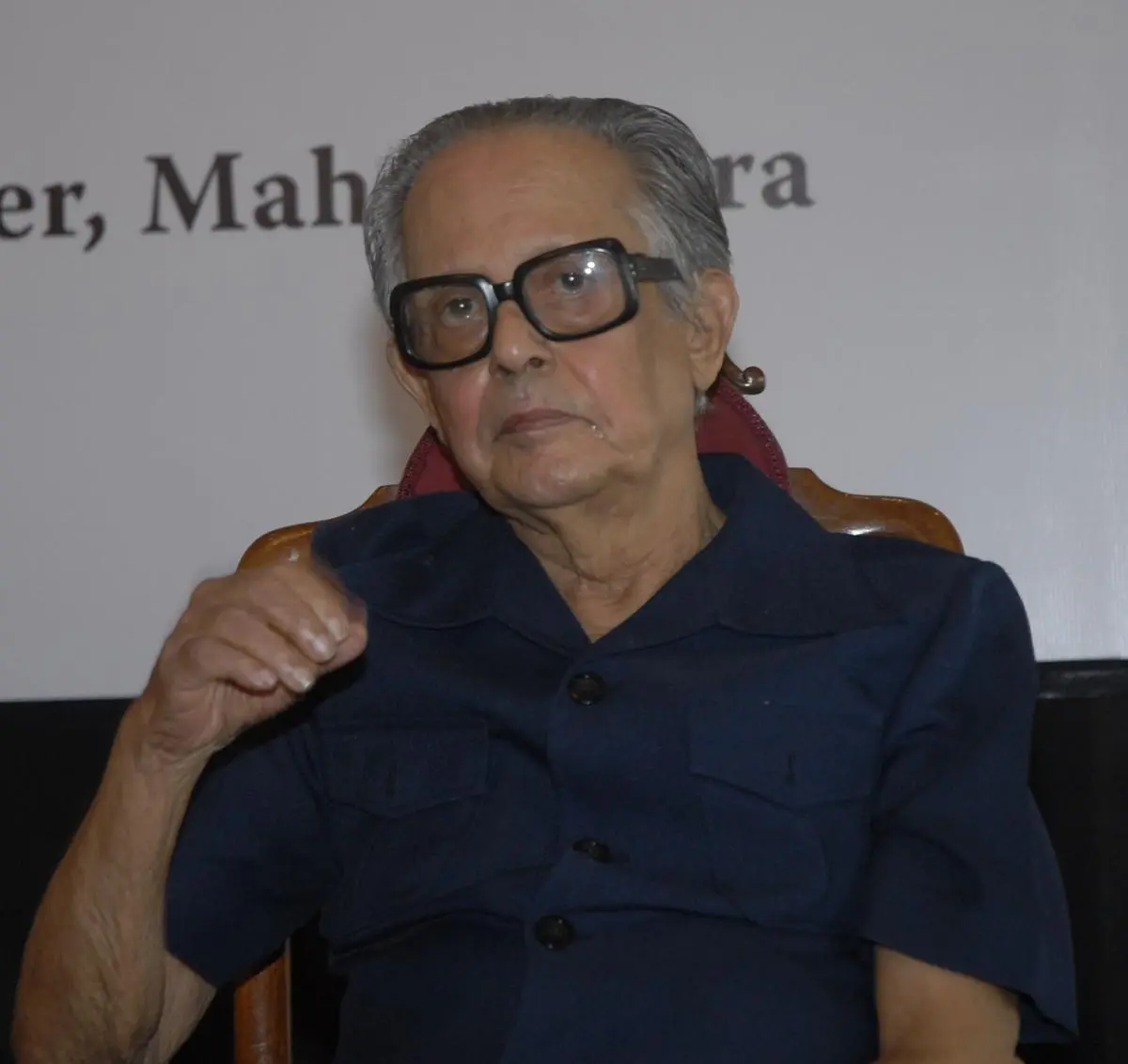

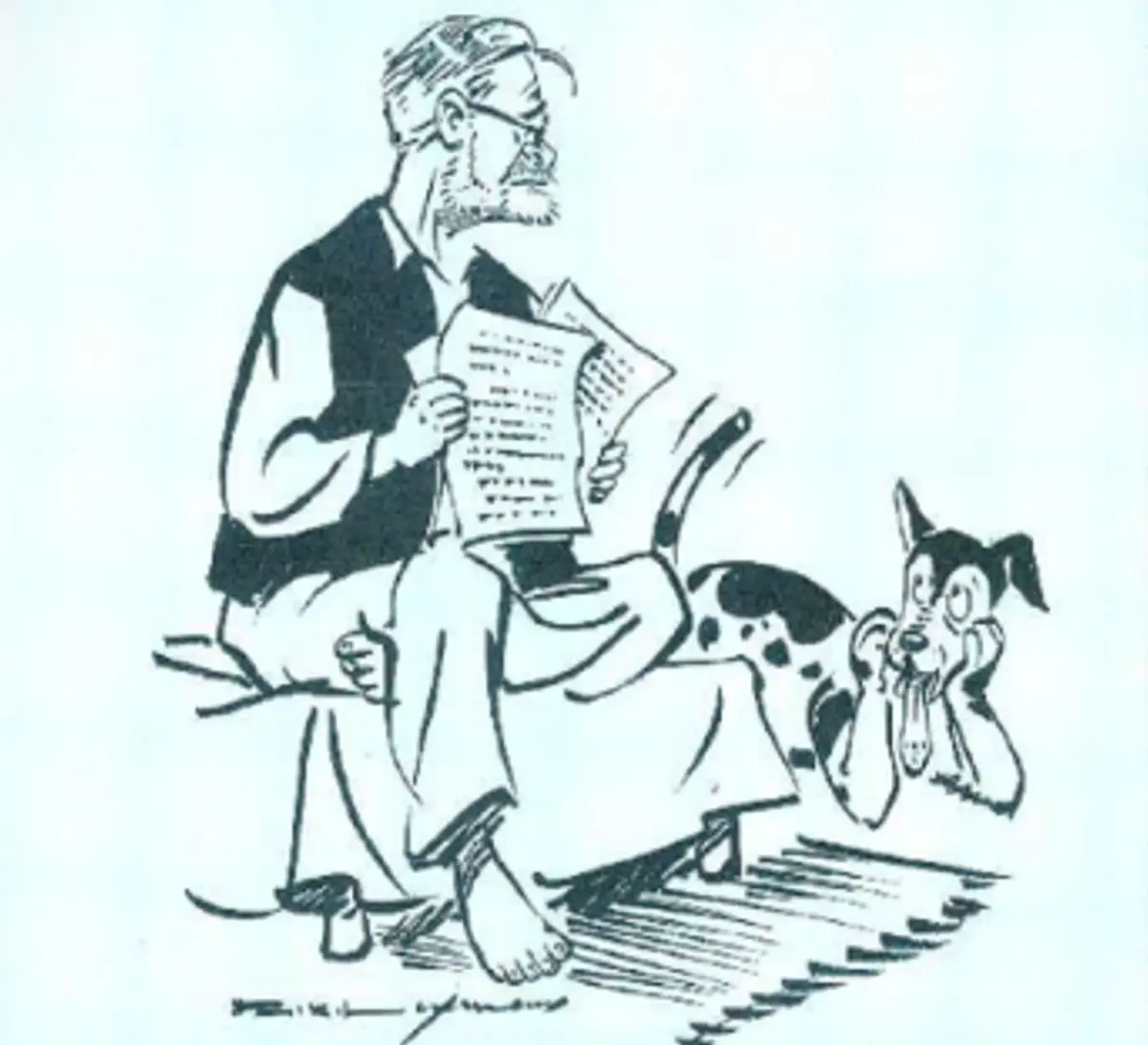

1992: R.K. Laxman

No Indian cartoonist’s style is as instantly recognisable as R.K. Laxman’s. The creator of the iconic Common Man began contributing to Frontline in 1985, illustrating most of the short stories and columns of his elder brother, R.K. Narayan, as well as other sections. There is a delightful bit in E.P. Unny’s R.K. Laxman: Back with a Punch on the relationship between the two brothers: “At some stage, his older brother R.K. Narayan, already a published author, was asked to guide the budding artist, who was a good 15 years younger. The mentoring didn’t go beyond the periodic reminder that a handkerchief was a better option than the front of his shirt for wiping pencil and chalk stains.” Above is Laxman’s illustration for the Vijay Tendulkar column featured in the box below.

Find the illustration here.

Photo Credits: Vivek Bendre

Here is Laxman’s illustration for the Vijay Tendulkar column featured in the box below.

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Archives

1992: Vijay Tendulkar

The second issue of August 1992 introduced the playwright’s column “Provocatively Speaking”. Its first instalment was titled “My dog on Indian journalism: With special reference to English column-writing” (August 28, 1992). An extract from the portion where the writer’s dog offers his critical opinion on journalistic writing.

Any journalistic writing worth the name must have a stance. Otherwise how would it bark? And bite? And wag its tail in case a need arises? Stance is something basic to what you write as a journalist. That makes your writing lively, forceful and aggressive. Magnificently notorious. It adds colour to the boringly plain and lacklustre arguments like the ones you have put in your writing. (And what interesting arguments can one produce day in and day out?) The stance, the cavalier style, the excitement of shadow-boxing with a real or imagined enemy make even the most unreadable matter worth a read. Therefore, include a stance in addition to bark and bite. And, of course, a tail to follow it.

Read the column here.

Photo Credits: Special Arrangement

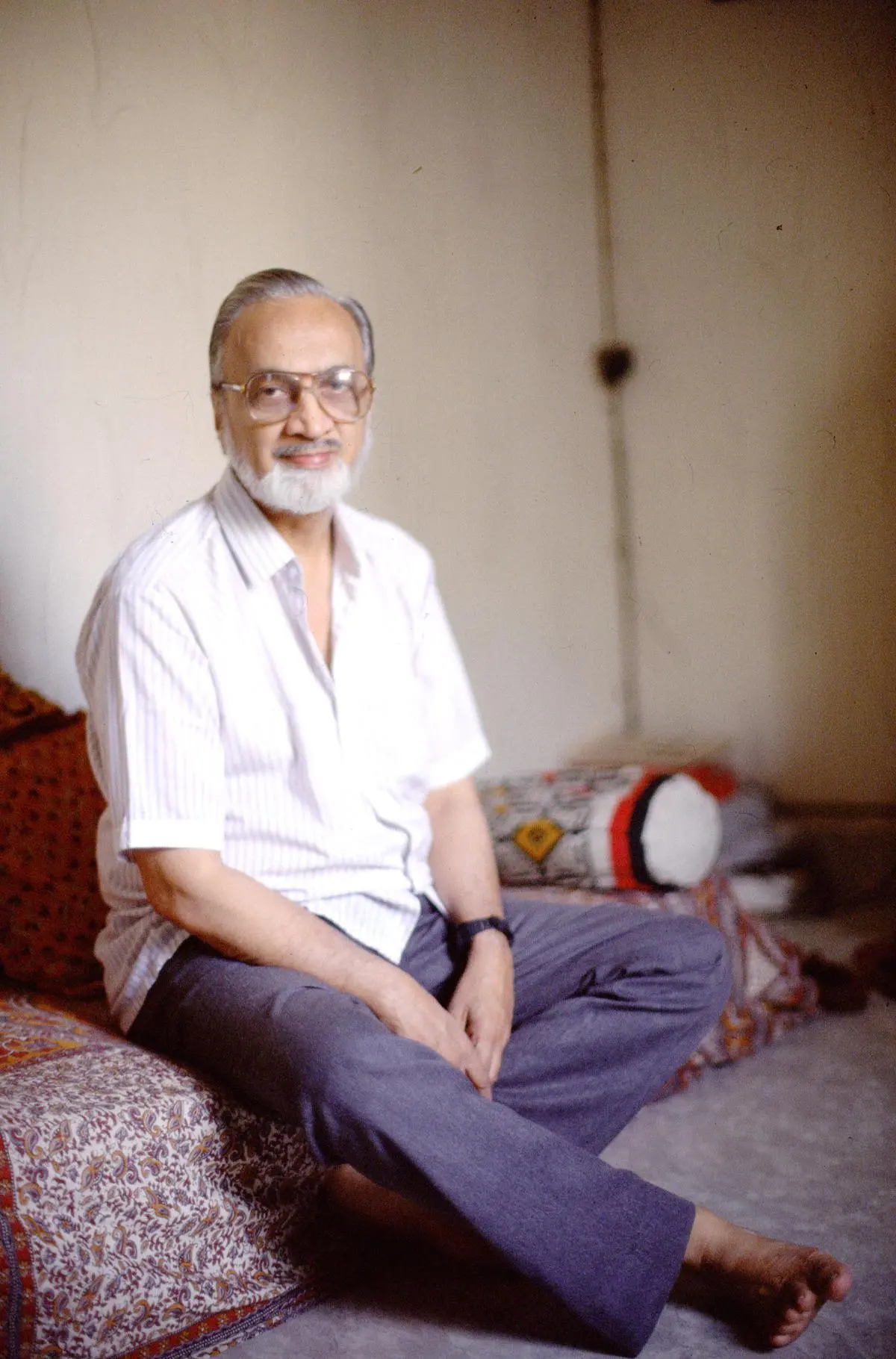

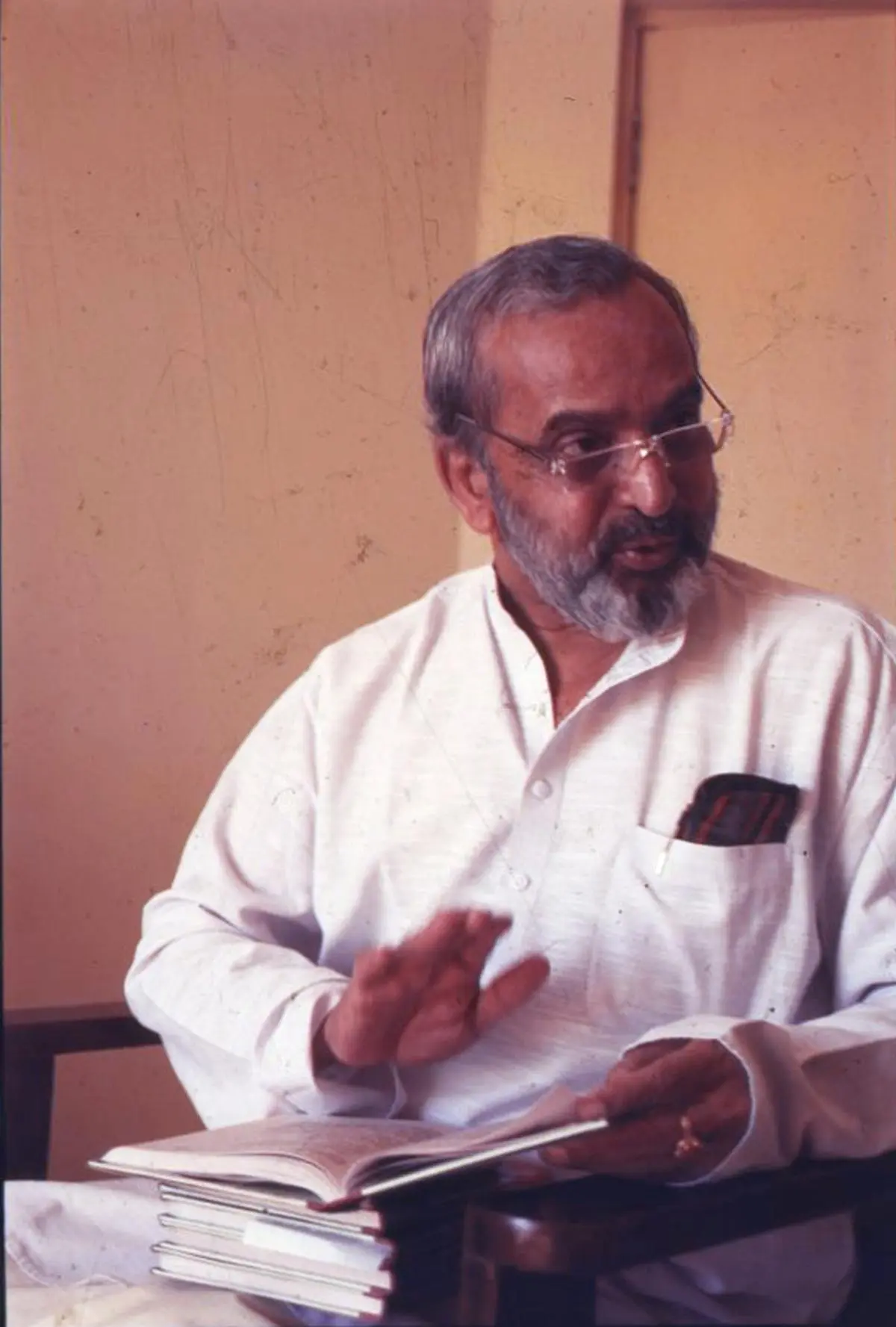

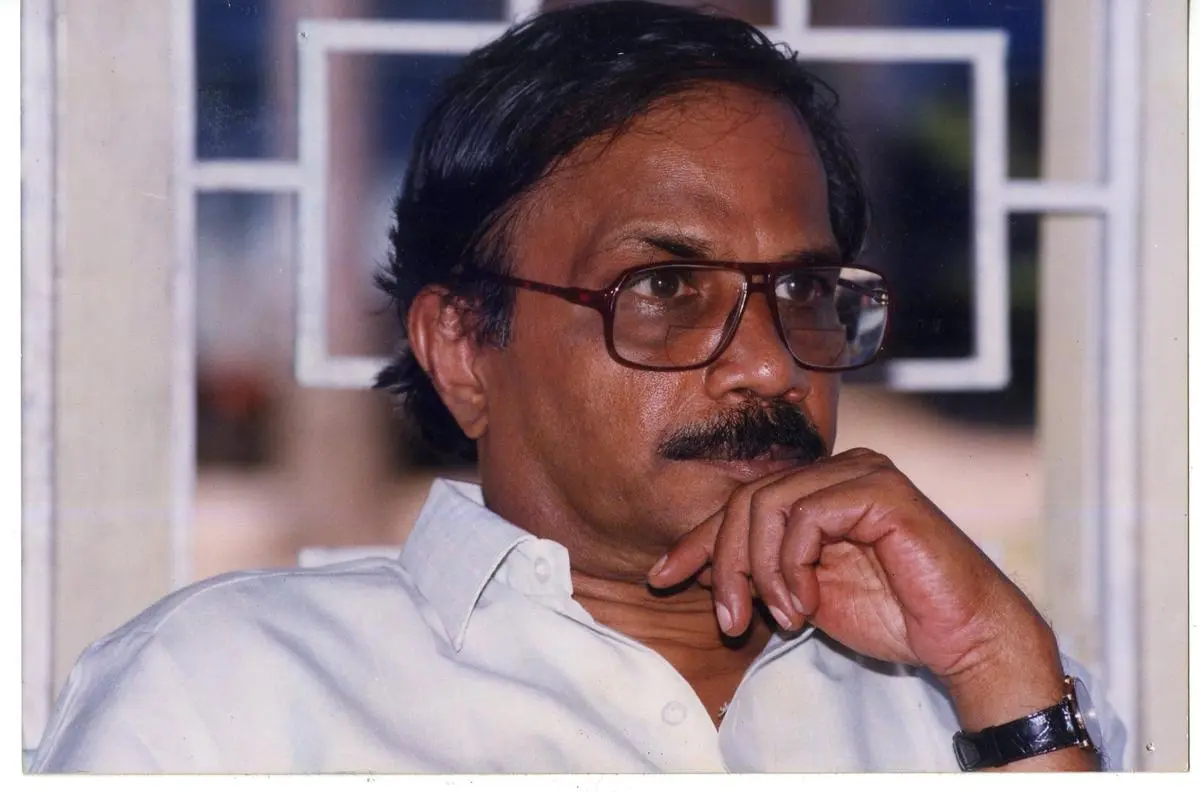

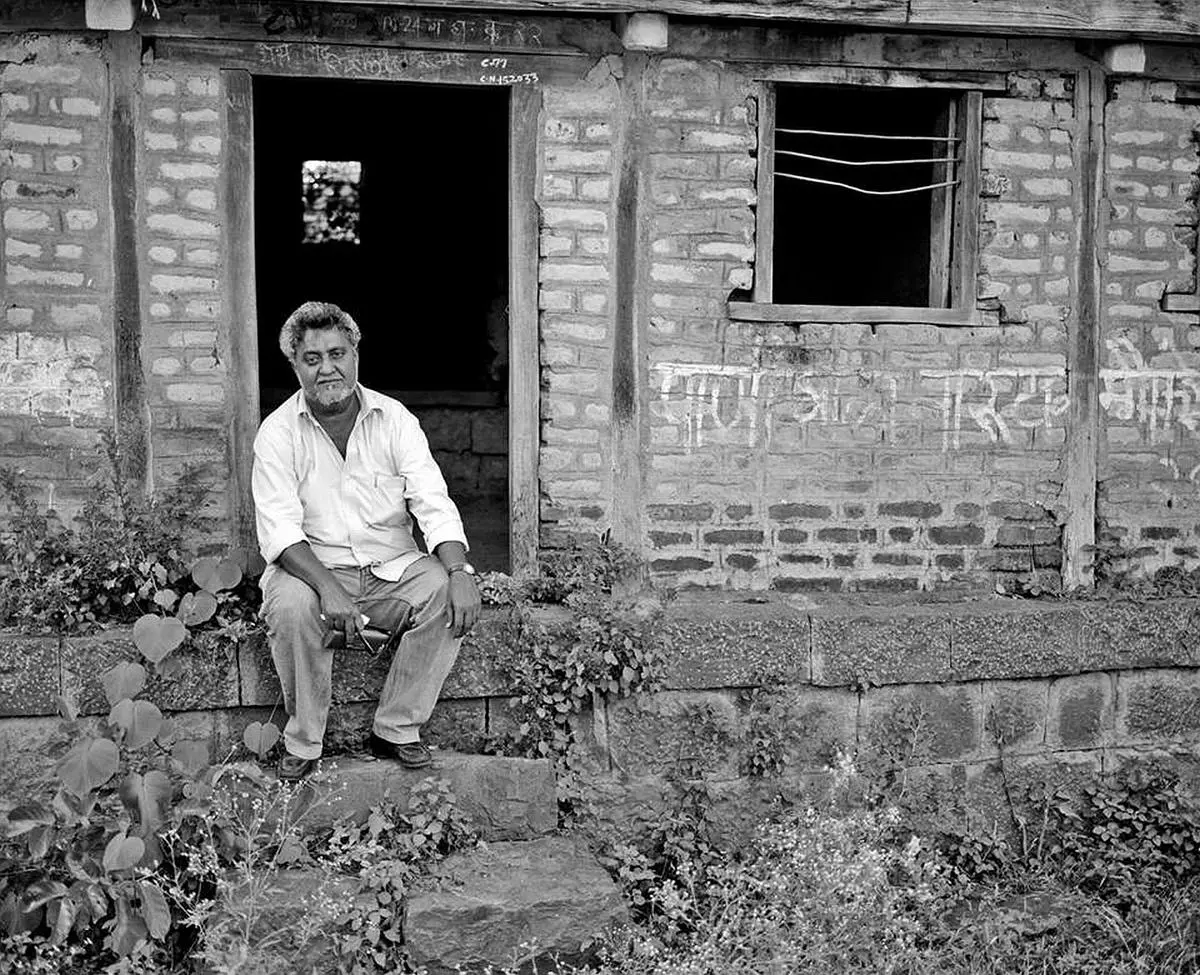

1995: U.R. Ananthamurthy

In 1994, he won the Jnanpith Award, the sixth Kannada writer to be so honoured. He discussed his groundbreaking novel, Samskara; the Navya movement in Kannada literature; and socialism in an interview with Chetan Krishnaswamy (“A quarrel with myself”, January 13, 1995).

Q: What made you write Samskara?

A: All writers have a quarrel with themselves, a quarrel in the deepest sense of the term, with their own culture. A quarrel with yourself is not very different from a quarrel with your culture, which is mainly what you are. And you begin to realise your inner strength as well as your radical looks. I began to see that my culture was inadequate to meet the challenges of the modern times. And the quarrel I had was a lover’s quarrel. It made me write.

Read the interview here.

Photo Credit: The Hindu Archives

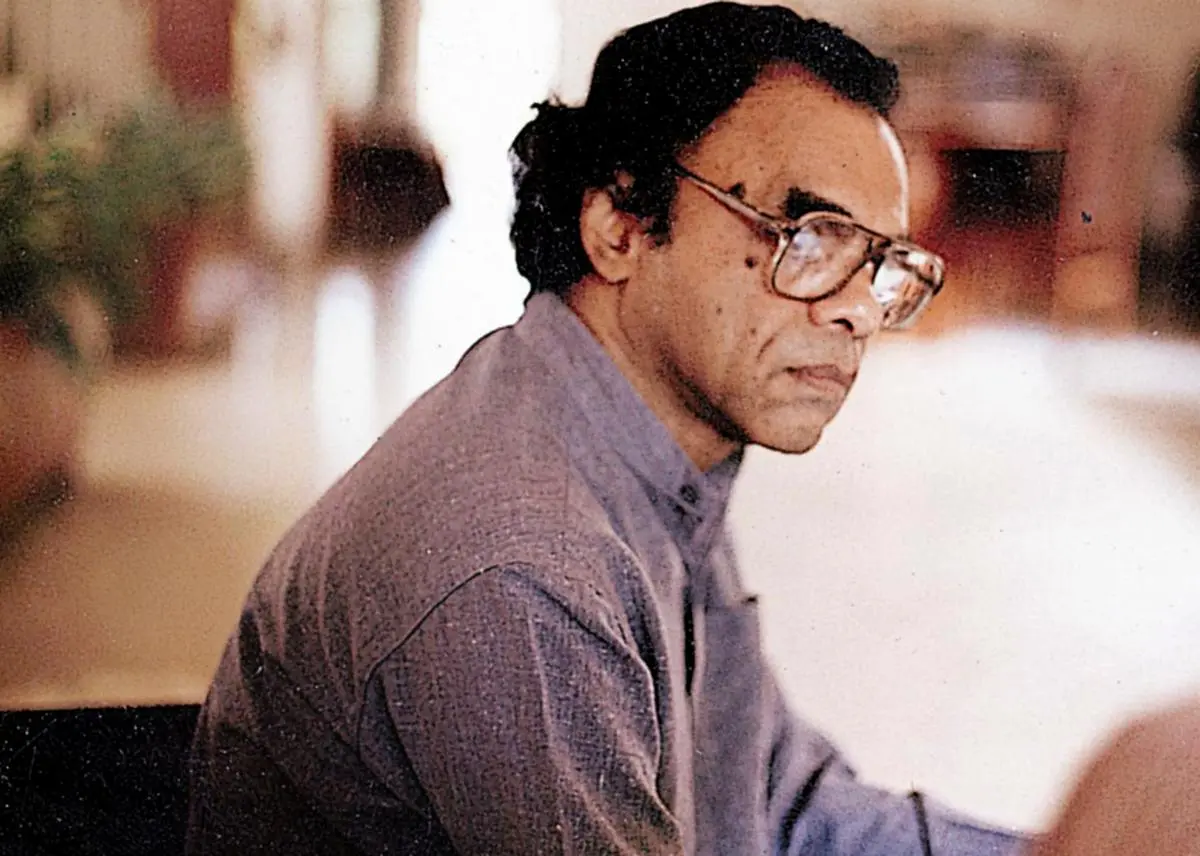

1995: Mani Ratnam

His Bombay released on March 10, 1995, after being stuck with the censors for weeks, banned in at least one country, praised and reviled alternatively by political groups. The headline of his interview with Sandhya Rao—“Censor Board is obsolete” (June 2, 1995)—gave an inkling of his opinion.

Q: Do we have the maturity to do away with the Censor Board?

A: Why do we underestimate our audience? Why do we think we always have to protect them? That we know better, that we have to guide them? Why do we treat our audience like cattle? This is exactly what happened with the censors. After the movie they said, “Yes, we understand but will the common man understand? He will get charged up, he will go into the streets with knives….”

Where does this happen, you tell me? The man in the street is very well aware of what he wants and what he doesn’t want. It’s time we stopped over-protecting them, treating them like they cannot think for themselves. They vote, don’t they? They decide which government should rule, don’t they? Can’t they decide what film to see?

Read the interview here.

Photo Credits: By Special Arrangement

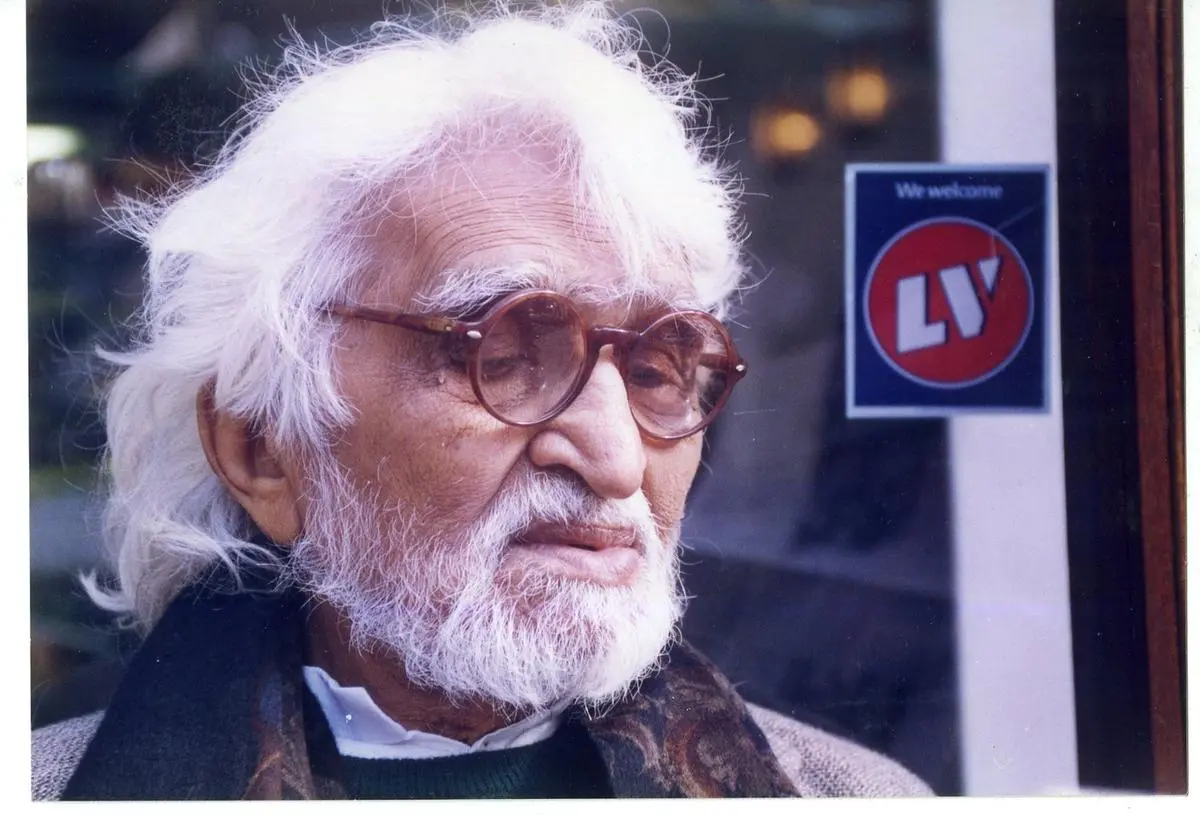

1996: Mulk Raj Anand

In a perceptive interview (“Being truthful to the echoes of the mother tongue”, January 12, 1996) with the literary scholar K.D. Verma, the acclaimed novelist talked of the caste system, existential despair, and the consolations of philosophy.

In all talk about tradition and modernity, few people have tried to see what tradition is and what modernity is. For instance, currently, traditionalists have revived the myth of God King Rama, the hero of the epic Ramayana, who is supposed to have lived 5,000 years ago, as the source of Indian tradition. This mindless and vulgar revival of the myth of the hero who won a war against the demon king of Lanka, has actually been used by decadent Hindu casteists and communal groups as a weapon in the political struggle to come to power in the name of Hindutva, or the Hindu nation. They have been fairly successful by using strong-arm methods, hatred and revenge against the Muslims in India for their alleged crime in having brought about the Partition of the country in 1947.

This is one kind of misuse of tradition, based on a complete misconception of what the Hindu tradition is, and it is posed against Nehruite secular social democracy, based on the demand of human rights for all.

Read the interview here.

Photo Credit: The Hindu Archives

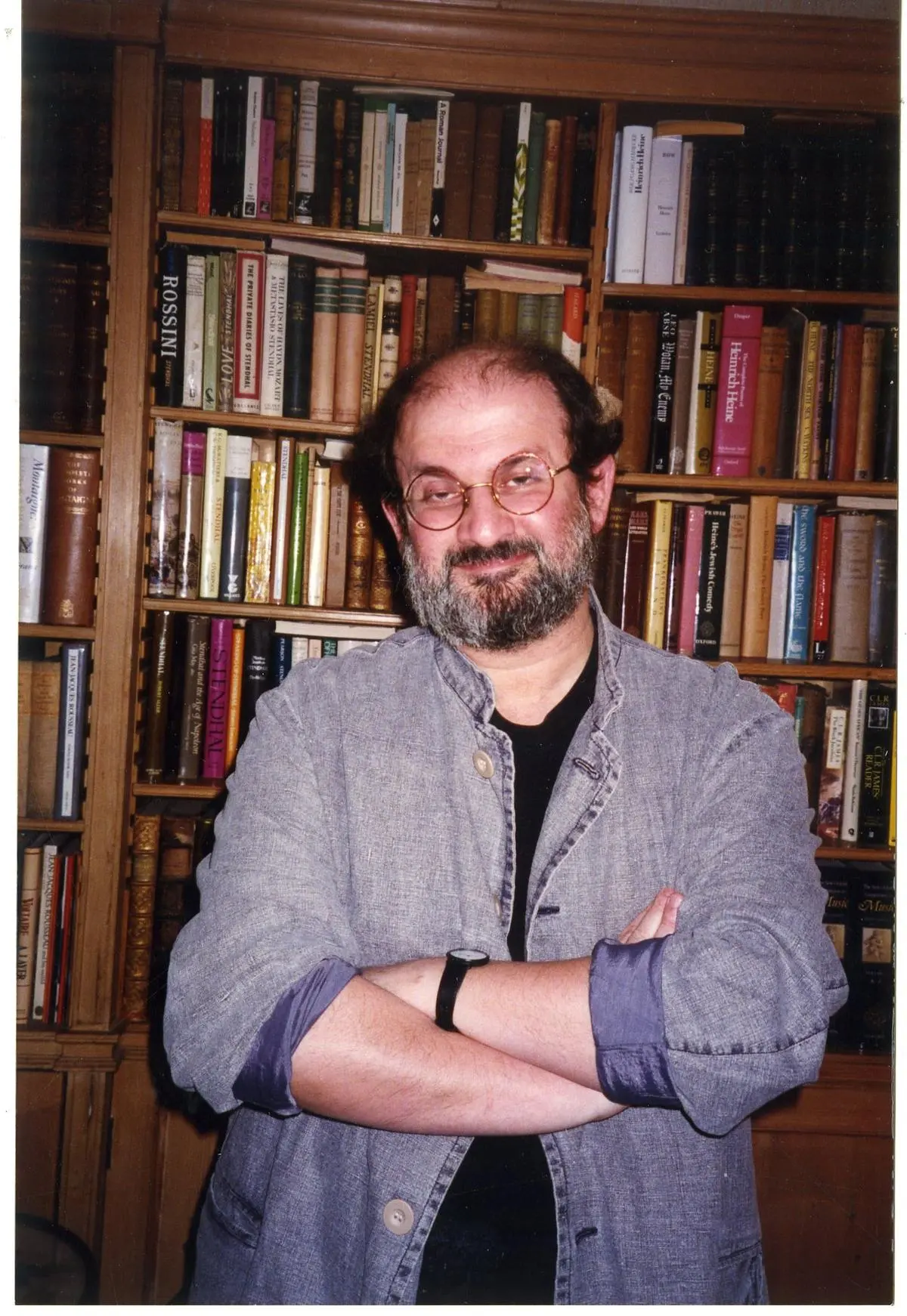

1996: Salman Rushdie

The writer, who needs no introduction, in a chat with N. Ram, the then Frontline editor, at his London home (“In conversation with Salman Rushdie,” May 3, 1996).

I remind [Rushdie] of the insights offered by Imaginary Homelands, that splendid collection of Rushdie essays and criticism which came out in 1991…. Why not follow up on Indian politics? I press Rushdie… when can one expect to read more Rushdie analysis of socio-political India? Pat comes the answer, “Can’t do it without visiting India.”

The obvious suddenly hits you: the greatest deprivation for this combustible, yet surface-cool man who is arguably the most original, imaginative and powerful talent working in the English language today is this sudden disconnection from India, imposed by the Ayatollah’s February 14, 1989 death sentence by fatwa. Rushdie manages to keep in touch, reads widely on Indian affairs and will surprise you with how much detail he has on… the emerging shape of socio-political India. But there is no getting away from the profound loss, the withdrawal of direct access.

Read the interview here.

Photo Credit: The Hindu Archives

1996: M.F. Husain

The artist spoke to Parvathi Menon from London after the destruction by Bajrang Dal stormtroopers of works such as his series on Hanuman, the Madhuri Dixit serigraphs, the Last Supper, and several tapestries. An extract from the chat (“This is an attack on progressive thinking”, November 15, 1996).

Q: Did you have any inkling of the plan by Bajrang Dal activists to destroy your paintings? What is your response to what happened?

A: No, I never expected this. It is really ridiculous. But I must say this very clearly. For me it is the process of painting which is very exciting. That is why I paint in public, so that the public can share. Once I have done the painting and I have got that experience, then it is for the people of India to preserve or destroy it. I have no regrets whatsoever. Because these are certain things that happen in such a great country, with so many diverse opinions. It is a minor thing. It should not be made into a big issue.

In a big family there are some children who make noise. But when they grow up, they will understand. So I am not at all angry with them. For they will come to know in time what is right and what is wrong.

Read the interview here.

Photo Credit: Mustafa Husain

1997: M.T. Vasudevan Nair

An excerpt from “Kadugannawa: A Travel Note”, a Malayalam short story by the Jnanpith award winner M.T. Vasudevan Nair, first published in July 1995. Translated by V. Abdulla (March 21, 1997) exclusively for Frontline, it is about an Indian journalist visiting Sri Lanka.

The announcement to board the flight came. The tourists got up and rushed towards the gate. Even the saffron-clad woman bhikshu did not lag behind.

A young man, who stood beside him, laughed and said: “Look at that.” He too laughed.

“To Kalambo?” the young man asked.

“Yes.”

“How’s the climate there?”

What climate was he talking about? The insurgency or the weather?

“I’ve no idea.” He made a mental note—one should not say “Colombo”; it was “Kalambo”.

Read the short story here.

Photo Credit: The Hindu Archives

2001: A.K. Ramanujan

A.L. Becker and Keith Taylor interviewed AKR at the University of Michigan in 1989, while he was teaching there. Excerpt from the interview published in Frontline (“An interview”, April 13, 2001).

So you are, in various ways and from childhood on, exposed to more than one culture. I have literally lived my life in three different cultures, although they are connected. I think it is in the dialogue of these three cultures—which I sometimes refer to as downstairs, upstairs, and outside the house—and in the conflict between these three languages, that I am made. That’s not special to me.

About 10 per cent of India is bilingual. If they happen to be educated, they will be trilingual.

KT: Let me see if I have the metaphor right. The downstairs language would be Tamil?

Tamil. Yes. The language of my family. Kannada would be the language of the city, Mysore, the language outside the house. English would be upstairs.

ALB: Upstairs would be the father?

Yes. I sometimes call them father tongues and mother tongues. My father was a mathematician. He did much of his work in English, and he literally lived upstairs. His library was there.

Read the interview here.

Photo Credit: The Hindu Archives

2003: Nayantara Sahgal

An extract from the piece “Wars and ‘peace’: The road to Iraq” (July 18, 2003), by the journalist and writer who won the Sahitya Akademi Award in 1986 for her English novel Rich Like Us.

A textbook of European history prescribed for my college course in the 1940s defined the noble purpose of the mandates: “Great Britain and France undertook to guide the Arabs toward political independence and membership in organised international society.” In Glimpses of World History, Jawaharlal Nehru described this arrangement as comparable to appointing “a tiger to look after the rights of a number of cows or deer”. Rights, political or human, did not in any case enter the picture. The British government saw no need to consult Palestinians when it announced it would establish a Jewish National Home on Palestinian soil.

Read the article here.

Photo Credit: By Special Arrangement

2004: Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay

She was a feminist long before feminism became fashionable. An extract from Amulya Gopalakrishnan’s tribute (“Woman with a Mission”, January 16, 2004).

In 1936, Kamaladevi became president of the Congress Socialist Party. Through her long involvement in the freedom movement, she stuck up for women’s rights, standing up to veterans Motilal Nehru and C. Rajagopalachari.

In fact, when Mahatma Gandhi opposed the inclusion of women in the salt satyagraha march (claiming that Englishmen would not hurt women, just as Hindus would not harm cows), Kamaladevi spoke out against this stand’

….

After Partition, Kamaladevi threw herself into humanitarian service, drawing up a refugee rehabilitation model based on the principle of cooperation. While Jawaharlal Nehru dismissed her ideas as “one of those newfangled plans that the Socialists would think up”, Gandhi gave her the go-ahead on the condition that she did not ask for state assistance.

The Indian Cooperative Union, despite huge obstacles, finally managed to create an industrial township called Faridabad on the outskirts of Delhi, founded entirely on community effort. Inaugurating the township, Nehru said he wanted India “to be a cooperative commonwealth”.

Read the article here.

Photo Credit: The Hindu Archives

2004: Ranga Shankara

Envisioned by Arundathi Nag in memory of her husband, Ranga Shankara is one of Bengaluru’s best known theatre spaces. An excerpt from “A theatre of one’s own” by Keval Arora (December 3, 2004):

Ranga Shankara was never intended as just another building that houses an auditorium which performers can hire to stage productions that spectators then pay to watch. It is because the practice of theatre is usually shaped by financial transactions of this sort that even the best-run of the theatre auditoria in India are today reduced to soulless shells.

If theatre is to survive the assault of other media in urban centres, it can no longer entrust its future to a simple momentum of this kind. At a time when more multiplexes are being commissioned in a single year than performance spaces in the last two decades (at a conservative estimate), theatre activity can flourish only when it is nurtured through enlightened sponsorship—be it in terms of finance, voluntary effort, or a sensitive appreciation of the difficulties that confront amateur and professional theatre workers. Ranga Shankara holds out such a promise.

Read the article here.

Photo Credit: K. Bhagya Prakash

2005: Homai Vyarawalla

India’s first woman photojournalist, who otherwise let her pictures do the talking, spoke to Dionne Bunsha about her life and work (“History, in black and white”, August 26, 2005). An excerpt.

I was not a part of the freedom movement. I took pictures of freedom fighters and covered most of the big meetings….

I knew all the big leaders very well. I also covered Lord Louis Mountbatten and all the functions he attended. Panditji (Jawaharlal Nehru) was very photogenic. He had different moods and was very active, so that made it possible to get good pictures of him. He always pretended as if no photographers were around. He didn’t mind if he was taking a nap and you took his picture. He would wake up and give you a smile. There were others who would flare up and ask for the film. He was not like that; he was so dignified.

Each one of them had a different personality. Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, Lal Bahadur Shastri, Nehru. It was fun taking their pictures.

Dr S. Radhakrishnan looked so imperial, he looked like a real President. You could see the integrity in their faces.

The papers publish the pictures of today’s leaders. They look so wily.

Somebody asked if I would want to take pictures today. I said no, thank you. When you have done the best, you can’t go to the mediocre.

Read the article here.

Photo Credit: By Special Arrangement

2007: Namdeo Dhasal

This Marathi firebrand loved to shock, both with his poetry and his politics. Sudhanva Deshpande reviews Dilip Chitre’s translation of Namdeo Dhasal’s verse (“Superstar Dhasal”, July 27, 2007).

There is something of a rock star in Namdeo Dhasal. He delights in shocking, in shaking up the staid, in stirring up controversies. The more his critics are exasperated, the more he enjoys being outrageous. Which is why it is intriguing that Dilip Chitre completely sidesteps Dhasal’s cosying up to the Hindu Right. Chitre writes a long introduction to the volume, follows it up with another essay on Dhasal’s Mumbai, and concludes with his delight and despair in translating the poetry; while all three pieces discuss Dhasal’s politics at some length, he never once mentions Dhasal’s support of the Shiv Sena or the RSS. Ordinarily, this would be called intellectual dishonesty. But Dhasal’s own political positions are so well-known—at least in Maharashtra—and he is so unapologetic about them, that one is simply amused at Chitre’s touching hope that readers will not notice.

Read the review here.

Photo Credit: Henning Stegmuller

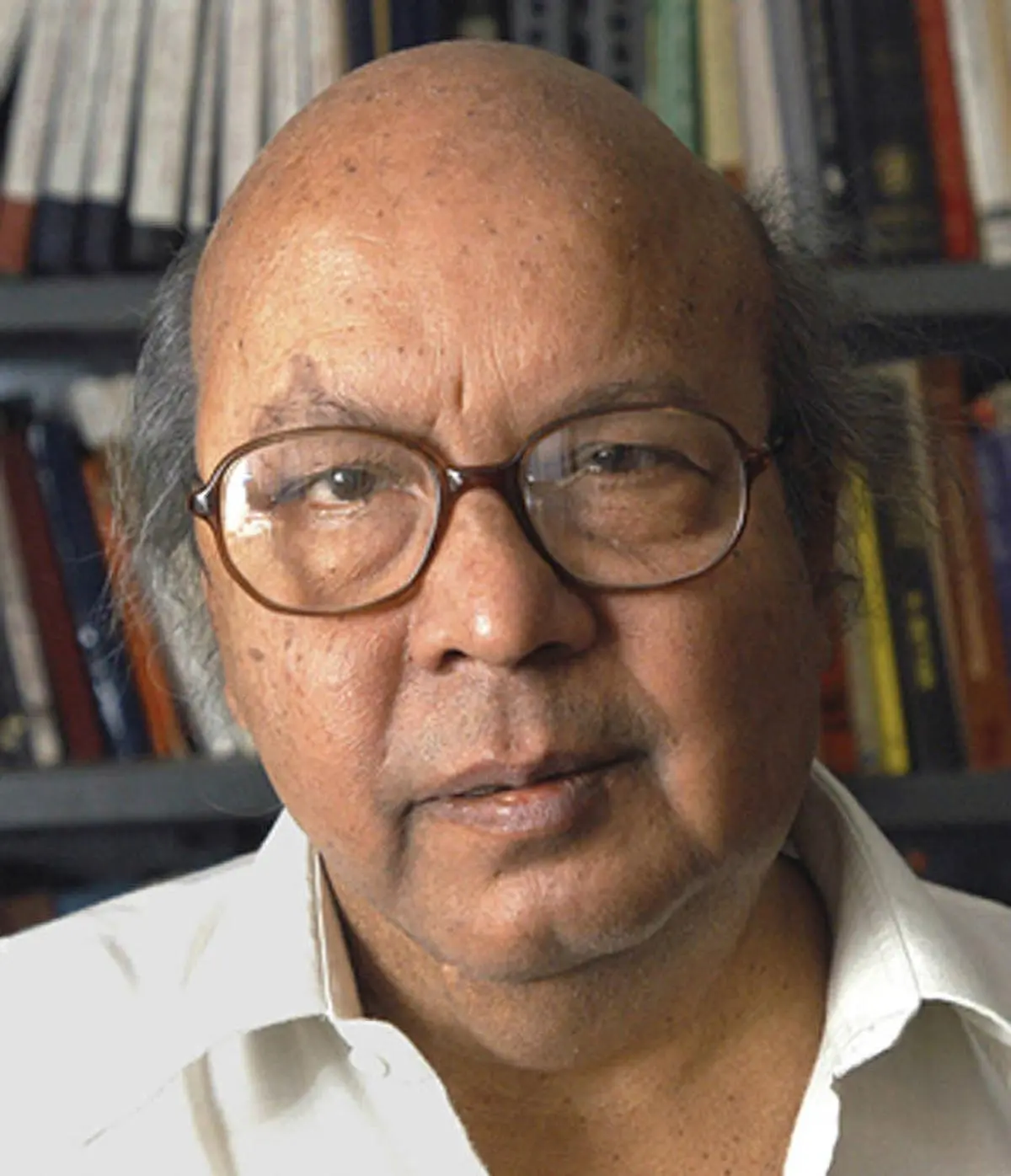

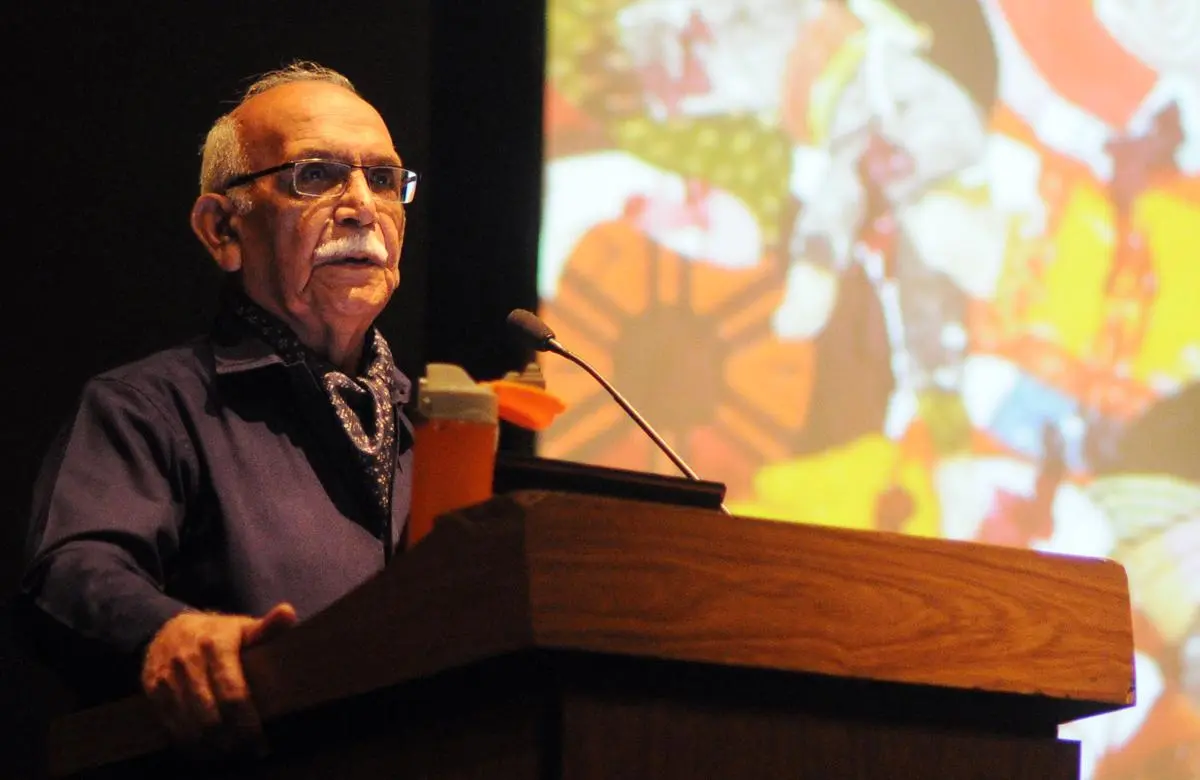

2009: Dwijendra Narayan Jha

Professor D.N. Jha was part of a team of independent historians who submitted an evidence-based report in 1991 rejecting claims that there was a Hindu temple underneath the Babri Masjid. Here is an extract from his interview to Ajoy Ashirwad Mahaprashasta (“State should rely on historians”, December 18, 2009).

Q: Could you briefly tell us the findings of the independent report prepared by M. Athar Ali, Suraj Bhan, R.S. Sharma, and you?

A: The Babri Masjid was built by Mir Baqi, a military officer [under] the Mughal ruler Babur, in 1528-29. The main contention of the Sangh Parivar is that the mosque was built by demolishing a Ram temple and that it was the birthplace of Rama. But it was only in 1948-49 that you see a miraculous appearance of idols under Gobind Ballabh Pant’s chief ministership [of the United Provinces] and Nehru’s prime ministership. Between then and the mid-1970s, one does not hear of this controversy at all. It was only after the VHP [Vishwa Hindu Parishad] came into being that it started talking about Kashi, Mathura, and Ayodhya as pilgrimage centres. Gradually in 1986, you see the opening of the locks [of the masjid] and, subsequently, the shilanyaas.

Read the interview here.

Photo Credit: By Special Arrangement

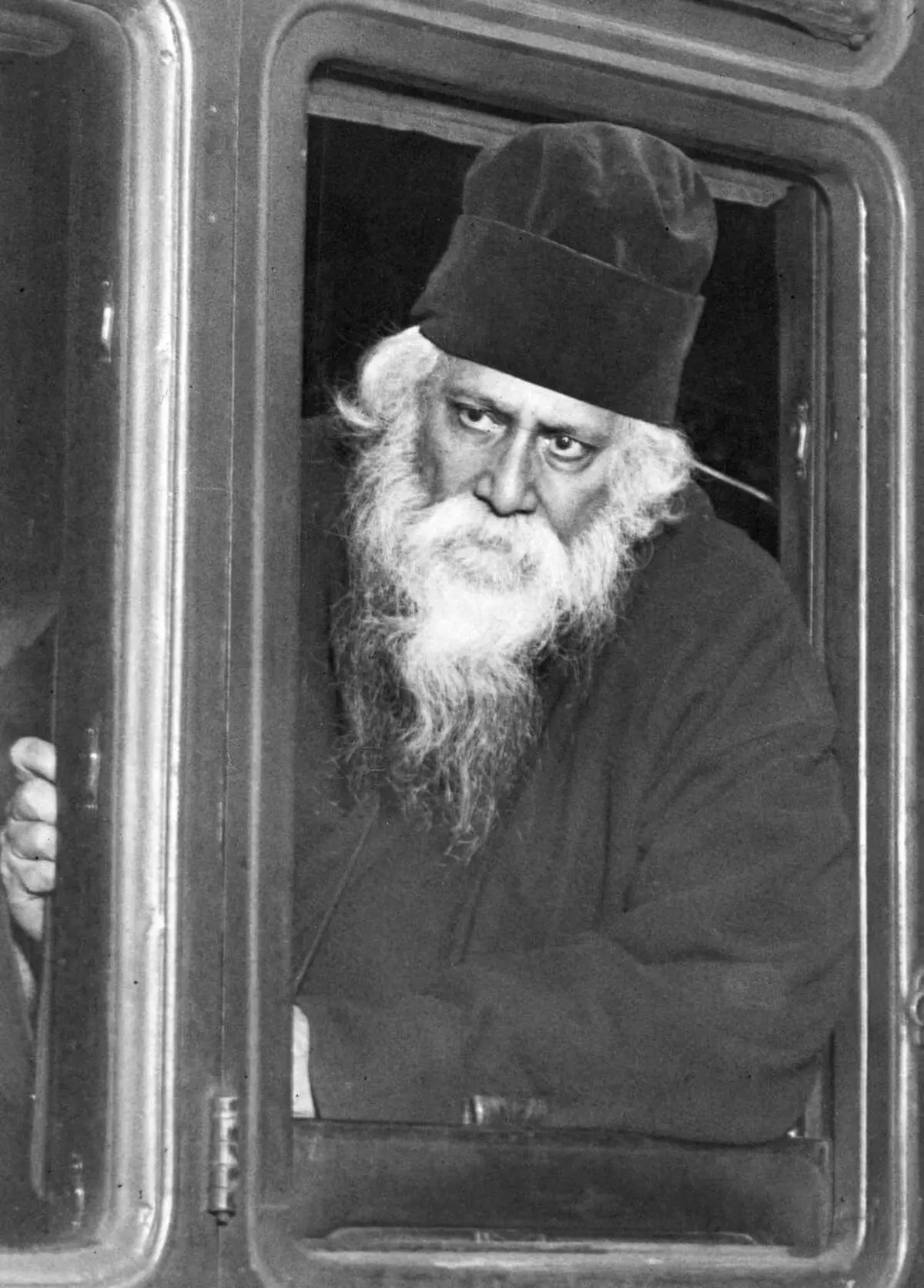

2012: William Radice on Rabindranath Tagore

This noted Tagore translator wrote a moving essay (“Timeless Tagore”, January 13, 2012) on the poet’s legacy and continuing relevance in an issue celebrating his 150th birth anniversary.

Let me end with Tagore’s own voice. I cannot do that physically in a magazine article, but it is not difficult now to find on the Internet Tagore’s own rendering of his song Tobu mone rekho…. Tagore wrote the song in 1887, and may not have been thinking of himself or his future legacy at all. But it is impossible to hear it now without thinking of the song as prophetic, and when I hear Tagore sing it himself, with the rhythmic flexibility that is such a feature of his poetry, prose and paintings, and with a heartrending catch in his voice in the last line, which suggests that he had a lump in his throat and was scarcely able to get through it, I know in the core of my being that Tagore was one of those creative geniuses who make one feel privileged to be human.

Read the article here.

Photo Credit: The Hindu Archives

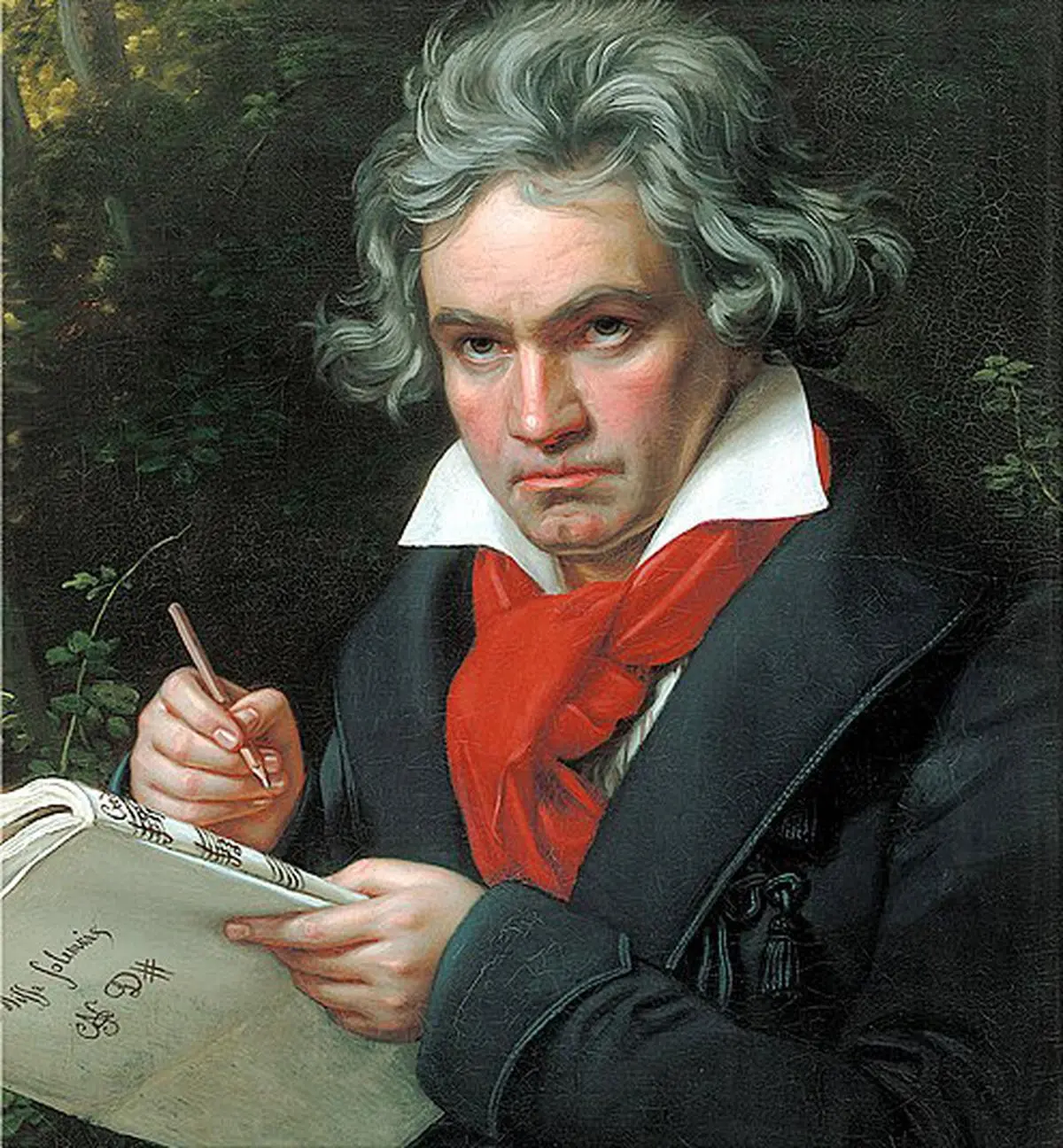

2012: Jayati Ghosh on Beethoven

The eminent development economist is also a connoisseur of Western classical music, and wrote about it in Frontline for many years. Here, she describes Beethoven’s music as a representation of our times (“Beethoven’s last quartets”, October 19, 2012).

Take the String Quartet Opus 131 in C Sharp Minor, which Beethoven himself considered to be among his best works and which is generally recognised to have a perfection that is beyond controversy (Robert Simpson writing in The Beethoven Companion, Faber and Faber, 1971). Richard Wagner described the first movement a fugue in which the four string instruments have separate voices that follow and then merge in a wondrous intermingling of supremely elastic and longing phrases as the greatest expression of melancholy in all music. Yet melancholy is a rather tepid and even misleading word for this music. It is indeed an expression of great tragedy, but so distilled that it almost seems to draw from that tragedy a pure and heart-wrenching beauty, a mystic vision of something that can only be called otherworldly.

….

This may be why it is so apt as a musical representation of our times: full of tragedy, injustice and farce, but also complex enough to be full of humour, love of life and (despite everything) hope for the future.

Read the column here.

Photo Credit: By Special Arrangement

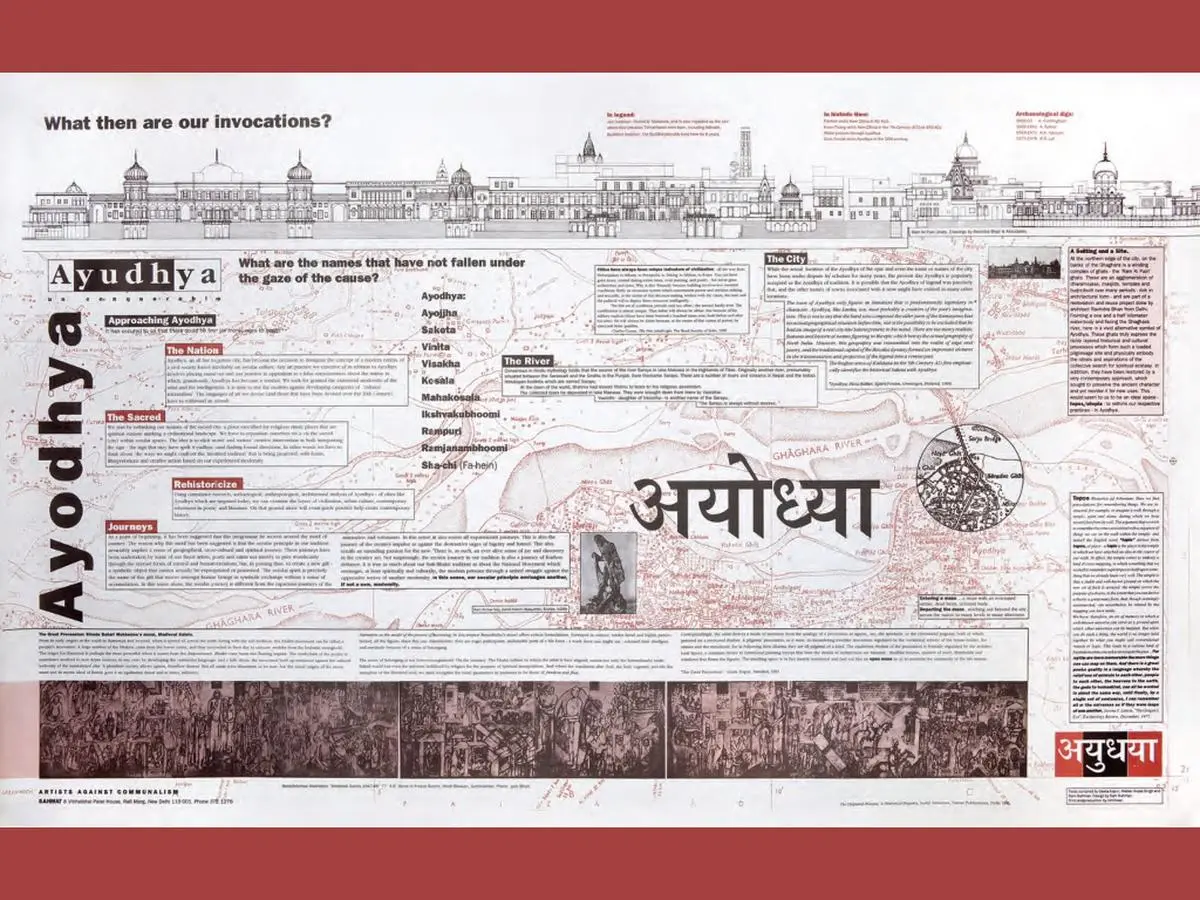

2013: Sahmat

Professor Anil Bhatti reviews a volume that traces 25 years of the artist-activist collective Sahmat (an acronym of Safdar Hashmi Memorial Trust, which also means “in agreement” in Urdu and Hindi) in “Mapping Sahmat” (May 31, 2013):

Sahmat adopts the Brechtian stance of singing in and of dark times. For Sahmat this means occupying the spatial and temporal domains that are threatened by the forces of reaction with the artistic, political and organisational means that emerge collectively out of these times.

The Sahmat Collective: Art and Activism in India since 1989 is a remarkable historical document. Photographs, programmatic essays and statements by artists, critics and academics have been collected by Jessica Moss and Ram Rahman to give plasticity to the extraordinary story of Sahmat.

…

[It] structures the focal points of the struggle: Ayodhya and the demolition of the Babri Masjid; fighting communalism and fundamentalism; reasserting secularism and affirming the syncretic traditions of India; reconsidering Gandhi; the battle against the distortion of history in textbooks; and defending free speech and artistic freedom, epitomised in the defence of the artist M.F. Husain.

Read the article here.

Photo Credit: The Sahmat Collective

2021: Andrew Robinson on Satyajit Ray

The author of Satyajit Ray: The Inner Eye wrote the lead essay for Frontline’s centenary issue on the master auteur (“A century of Ray”, November 5, 2021):

“I have a feeling that the really crucial moments in a film should be wordless,” Ray said on another occasion, while discussing the wordless ending of Charulata, which he regarded as probably his finest film. If one thinks of Pather Panchali, this dictum is true. When a scene could have been played out conventionally through dialogue, Ray preferred to find a telling countenance, gesture, movement or sound to express the emotions more dramatically….

What makes Pather Panchali a great film is, finally, that it speaks to us—whether we are Indians, Europeans, Americans, Japanese or whoever—not primarily through its plot, dialogue or ideas, but through its apparently inevitable current of ineffable images. No wonder the film director Akira Kurosawa commented: “Not to have seen the cinema of Ray means existing in the world without seeing the sun or the moon.”

Read the article here.

Photo Credit: Special Arrangement

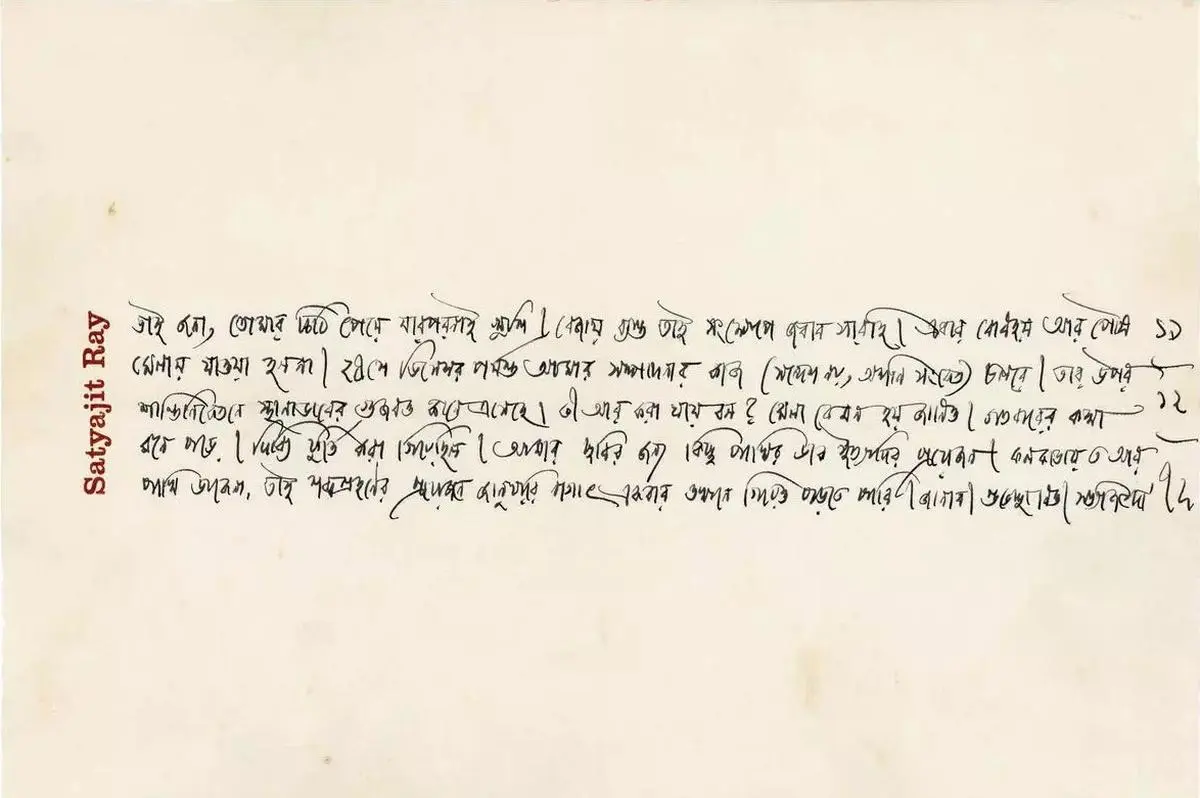

2022: Letters Satyajit Ray wrote

Juhi Saklani shines a light on Ray the prolific letter-writer in “A man of letters” (June 17, 2022).

It is remarkable that Satyajit Ray managed to be such a prolific letter-writer even as he was making films, scouting for locations, writing dialogues and lyrics, composing music, drawing costumes and sets by hand in his famous kheror khatas [red books], designing posters, running Sandesh [the children’s magazine], writing and illustrating the popular Feluda and Professor Shonku stories, writing articles, travelling extensively, and much more. But this propensity for the epistolary serves as the context for his 52 letters to Nilanjana Sen, recently published as the book Iti, Satyajit Da.

….

In 1970, Ray visited Santiniketan to make a documentary on his teacher, the artist Benodebehari Mukherjee. Young Nilanjana—“Jana” to all—was in her second year of college and already a big fan. She met him as well as Bijoya Ray [Satyajit Ray’s wife] twice, and wrote her first letter to him in 1972. Thus began a correspondence that lasted until 1988 when Ray became too unwell to keep up the usual pace of his life, and long-distance telephone calls took over. The letters, Nilanjana’s most prized treasures, were tucked away in her safe until recently when her brother-in-law, the sculptor K.S. Radhakrishnan, persuaded her to share them with the world.

Read the article here.

Photo Credit: Musui Art Foundation

2023: The 1980s’ feminist documentaries

Filmmakers Anjali Monteiro and K.P. Jayasankar write about the fresh and audacious perspectives offered by feminist documentaries of the 1980s (“Gazing as a feminist”, July 28, 2023).

The early 1980s witnessed feminist struggles across the country on the issues of rape, dowry, and violence against women; some of these struggles were in response to the patriarchal Supreme Court judgment on the Mathura rape case in 1979. This resistance to state and familial power found creative expression through street theatre, songs, posters, and photographs.

In 1980, Deepa Dhanraj, along with Abha Bhaiya, Meera Rao, and the late Navroze Contractor, formed the Yugantar Film Collective…. Yugantar worked with other feminist collectives such as Stree Shakti Sanghatana in Hyderabad and Saheli in New Delhi. The collective’s first project was a series of films on the unionisation and struggles of women workers in the informal sector, including 12 beedi workers in Nipani, Karnataka, and domestic workers in Pune.

….

In many ways, this space for women’s voices and their agency marked a radical shift in the language of Indian documentary, particularly Films Division work, with its voice-of-God voice-overs.

Read the article here.

Photo Credit: Siddharth Sengupta

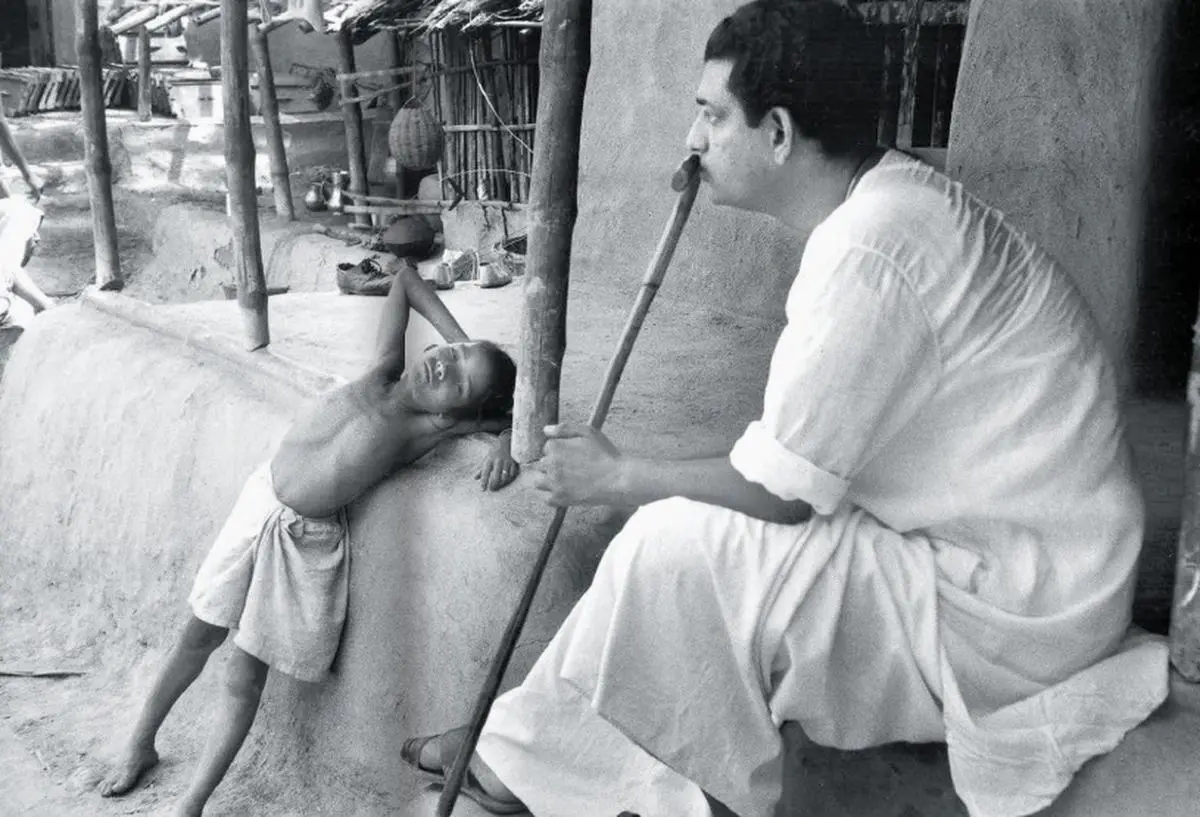

2023: Mrinal Sen

In a special issue that commemorated Mrinal Sen’s centenary year, Professor Madhuja Mukherjee draws attention to some of the recurring themes and motifs in his oeuvre (“Memory Mansions”, August 25, 2023):

Sen’s repeated emphasis on the continued deprivation of the working classes is woven even more intricately into the plot of Calcutta’71. The film opens with a fictive and dramatic courtroom sequence in which Ranjit of Interview (1971), played by Ranjit Mullick, is being judged for vandalising and disrobing a mannequin. This is preceded by a title and a voice-over (which appear in the film several times) stating that the character is 20 years old but has been walking for thousands of years through “poverty, gloom and death… and witnessing history; a history of poverty, deprivation and exploitation”. This is followed by a montage of contemporary city life in which old and new technology, gadgets, political movements of the day, and abject poverty, past and present, are spotlighted. Ranjit’s seemingly trivial vandalism is thus located within the larger context of a history of inequality.

Read the article here.

Photo Credits: The Hindu Archives

2023: Shahidul Alam

An excerpt from Ranjana Dave’s interview with the renowned Bangladeshi photojournalist-activist for whom photography is a means to achieving social justice (“Photography is a reciprocal event”, September 22, 2023).

Q: In the book, the camera is not just a visual implement but also a sensorial organ. You talk about how your camera learnt to love the smell of the streets. How does one photograph with the body?

A: I used to live in a place called Lalmatia (in Dhaka). I would cycle or walk to work. I found it amazing how that eight-minute walk was so special every time. Every little nuance, every nook and cranny, the pauses I make, the people I look at, the expressions, the looks, the hesitations along the way, were all rich and meaningful. That, to me, is what photography represents. The image is certainly an end product, but the journey is very important. Often, in a situation, I can smell a photograph. I know it is there. Not because I’ve seen it, but because I can smell it, look and probe, and hopefully find it.I think photographs need to be read in terms that go beyond the visual image in front of you. You see, particularly in family photos, not just what is in the frame but also beyond it. What makes the frame meaningful is the history, politics, dynamics, social structure that envelop the frame.

Read the article here.

Photo Credits: Sandeep Saxena

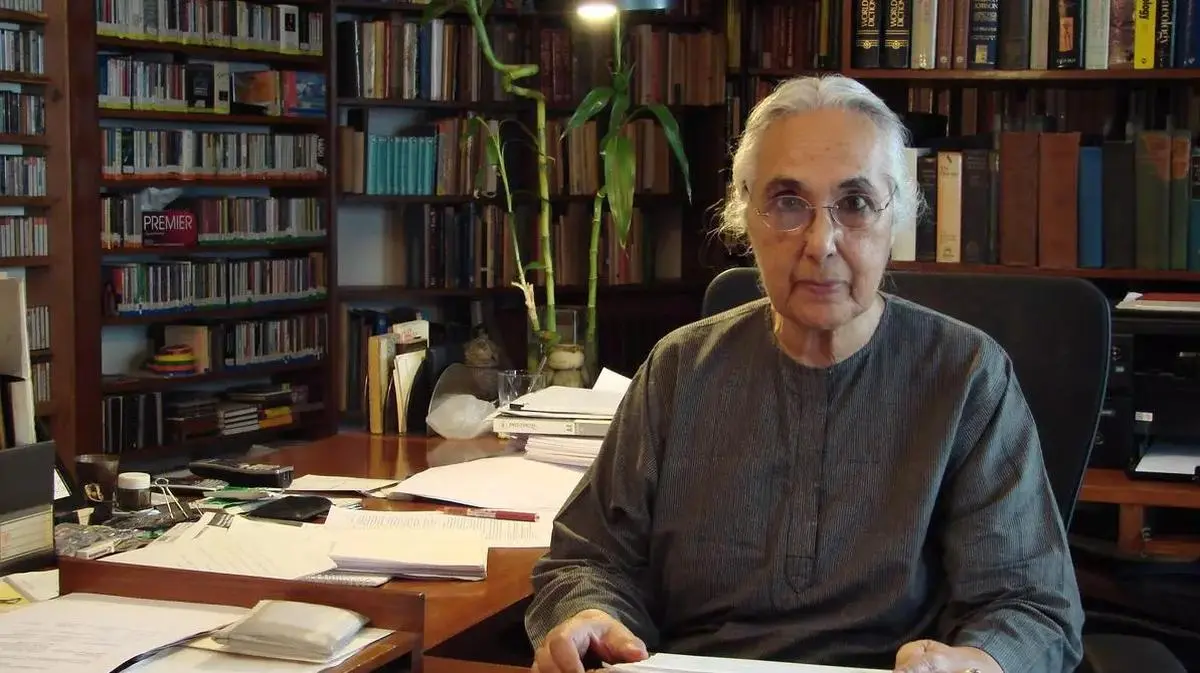

2023: Romila Thapar

A perceptive review of Professor Thapar’s Our History, Their History, Whose History? by S. Irfan Habib, who sees the book as a summation of her decades-old engagement with India’s historical past.

Nationalism in India today needs an enemy; it needs an object of hate to flourish in full relish. It longs for uniformity and hates any deviant behaviour or even questioning of its so-called nationalist premise. It abhors diversity of cultures, views, eating habits, dress, and even modes of entertainment. This paranoid nationalism, now patronised by the state, is the most lethal weapon being used against many of its citizens.

….I am reminded of a letter that Jawaharlal Nehru wrote on September 20, 1953. He was prophetic when he said: “[A] more insidious form of nationalism is the narrowness of mind that it develops within a country, when a majority thinks itself as the entire nation and in its attempts to absorb the minority actually separates them even more.” Romila has been conscious of this farcical history for very long, which is being peddled through social media such as WhatsApp, where a mere narrated story by you and me is claimed as history, particularly when these stories “become central to the most influential of current storytellers: namely, the media of every kind.”

Read the article here.

Photo Credit: The Hindu Archives

2023: B.N. Goswamy

Excerpted from Shanta Gokhale’s deeply appreciative tribute (“Master of the art of seeing”, December 15, 2023) to the art historian who was, first and foremost, a rasika (connoisseur).

“Miniatures are not to be seen from a distance,” he said. “They are to be held in the palms of the hands and studied with close attention.”

Take, for example, the miniature in which the dim shapes of trees articulated the space of a dark landscape, forming the background to the luminous presence of Radha and Krishna in the foreground. The lovers stood close together, lost in each other. “Look at the trees in the background,” Dr Goswamy said. “Notice that each of their trunks is split into two diverging branches. Now look at the two trees in the foreground, directly behind Radha and Krishna. What do you see? The trunks are not split. Not only are they whole, but they are entwined gracefully together like the divine lovers themselves. Even their colouring matches the lovers. One tree is dark like Krishna, the other light, like the golden-skinned Radha. That is how the mind and imagination of a painter works.”

Read the article here.

Photo Credits: NCPA Library

2023: Karan Johar

“The KJo phenomenon” by Ishita Sengupta deconstructs a quarter century of Karan Johar in Bollywood (December 29, 2023)

In 2023, 25 years since he began and seven years after he directed his last film, Johar helmed Rocky Aur Rani Kii Prem Kahaani. On the surface, nothing had changed…. Rocky Randhawa (Ranveer Singh) is a gym bro from West Delhi. Rani Chatterji (Alia Bhatt) is a political journalist…. Notwithstanding the mountain of differences between them, Rocky and Rani are pulled towards each other.

….

In any other Johar film, Rocky’s loud Punjabi tradition-bound family, where women do puja at home and men only talk to each other formally, would have occupied the narrative centrepiece. But here they are put under the scanner. It is Rani and her liberal-leaning family that lead from the front. They teach Rocky that masculinity need not look a certain way and they teach him enough to be critical of his surroundings and himself. Rocky Randhawa is the sole male character in a Johar film who questions Dharma’s indisputable stance: “It is all about loving your parents.”

Read the article here.

Photo Credit: Sujit Jaiswal/AFP

2024: Kattaikkuttu

Gita Jayaraj reviews Hanne de Bruin’s monograph titled Kattaikkuttu: A Rural Theatre Tradition in South India which places the art form within the larger context of Tamil cultural history. An excerpt from “Recording a tradition” (January 26, 2024).

The 10-day-long Paratam festival, with consecutive all-night performances of episodes from the Mahabharata, culminates in the killing of Duryodhana, a giant prone mud effigy struck on the thigh at the end of the last night’s performance to signal the slaying of the eldest Kaurava king and the end of the battle.

During this period, the entire village is converted into an off-stage performance space. The story is narrated every afternoon over several days, and the all-night Kuttu is performed over 10 nights.

The village is transformed, and everyday life occurs alongside epic time and space and larger-than-life kattai veshams at night. The book’s first section describes Kattaikkuttu and the various elements that are integral to it: veshams, characters, soundscapes, movement, performances, comedy, performance spaces, performers, audience ownership, and secular urban performances.

Read the article here.

Photo Credits: WWW.KATTAIKKUTTU.ORG

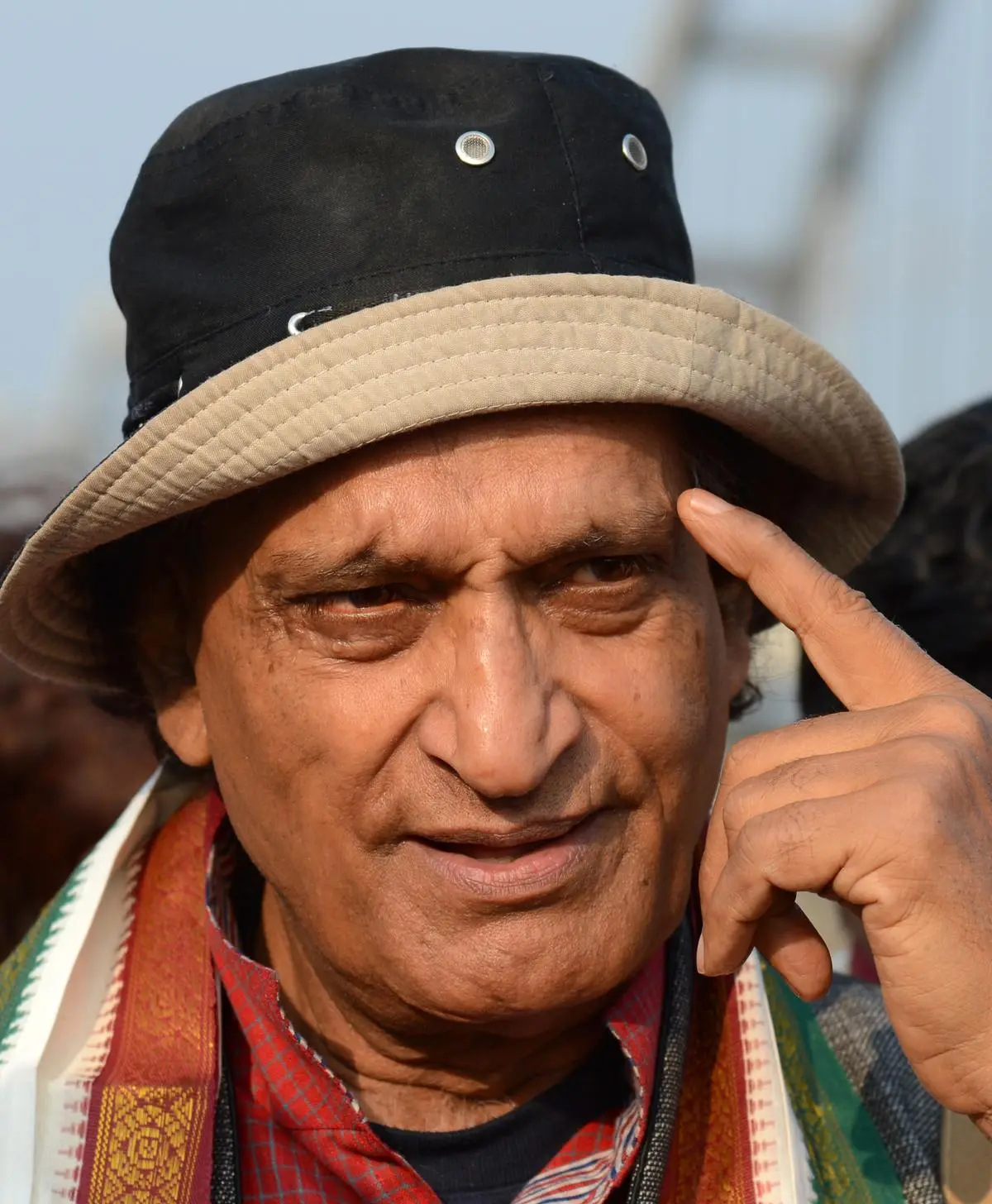

2024: Raghu Rai

He has been photographing India over the last 60 years. Three hundred images from his oeuvre were featured in the exhibition “Raghu Rai: A Thousand Lives—Photographs from 1965-2005” (February 1-April 30, 2024) at the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art in New Delhi. Editor and columnist Malavika Karlekar wrote on the exhibition (”Raghu Rai: Life in the raw”, May 17, 2024).

The exhibition rooms present a melange of everyday India, its streets, alleys, fields, shanties, and above all, its people. Many are scenes of existence in the raw. Of lives in the balance—cyclists weaving dangerously through four-wheelers, the not-so-young hanging out of buses, an ancient man trying to board an equally ancient Kolkata tram, stress writ large on his toothless face. There is an unforgettable image of Delhi’s Chawri Bazar—its chaos bringing alive the sounds and stress of hapless tongas, of boys hefting laden carts, of negotiations, arguments, of heat and dust. A quote from the photographer reminds one that such images are testimony to a changed cityscape, “a photo-history that cannot be rewritten”.

Read the article here.

Photo Credits: K.R. Deepak

Raghu Rai’s photograph from the lanes of Chawri Bazar, Delhi.

| Photo Credit:

Raghu Rai & PHOTOINK