Exotic Landscape (1910), oil on canvas by Henri Rousseau.

| Photo Credit: Wiki Commons

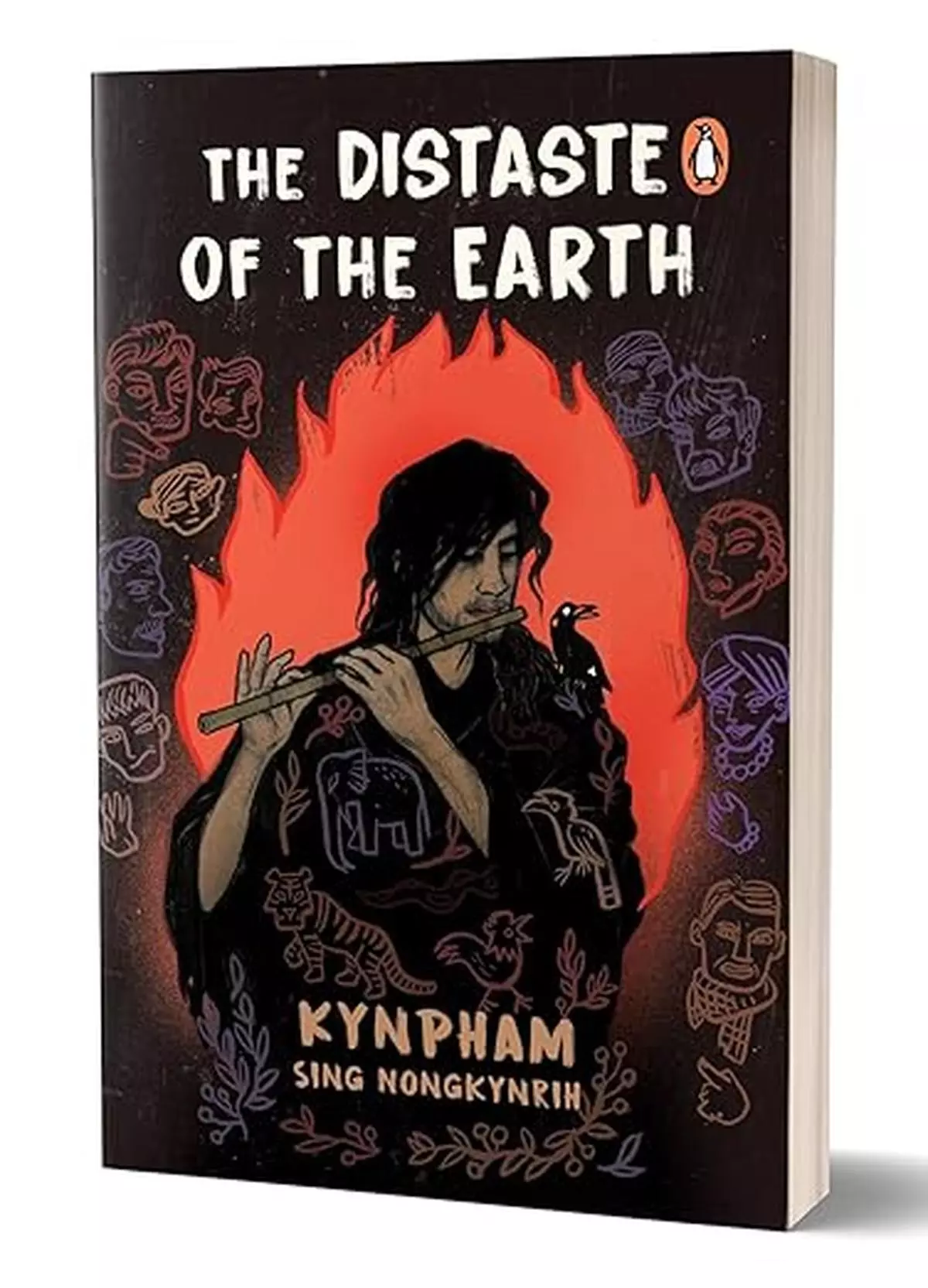

Kynpham Sing Nongkynrih’s enigmatically titled new book, The Distaste of the Earth, retells a Khasi folktale of star-crossed love. Similar to Funeral Nights (Context, 2021), which offered a documentation of the Khasi people’s traditional stories and cultural practices tied around the six-day feast of the dead called Ka Phor Sorat, the “true and tragic love story” of Manik Raitong (“Manik the Wretched”) and mahadei (queen) Lieng Makaw is the anchor of the present volume.

The tale holds a celebrated place in Khasi culture. Born into privilege, groomed as a great warrior but devastatingly betrayed by his clan, Manik lives as a recluse in sackcloth and ashes, renouncing the material wealth that had been the root of his misfortune. This pauper-prince does possess, however, the eternal and irresistible power of music and wields his sharati (flute) like an otherworldly sceptre. Manik’s soul-stirring music makes the wife of the powerful ruler of the largest hima (“state”) of Khasi antiquity succumb to its enchantment with inevitable tragic consequences.

Anthropologic imagination

Manik is Orpheus-like for the Khasi people, and his story is a mythic archetype. No wonder then that it exists in numerous tellings, not least by the author himself in Around the Hearth: Khasi Legends (Penguin, 2007) and Manik, A Play in Five Acts (Dhauli Books, 2018). Why, then, does it bear repeating? The answer possibly lies in another myth that Nongkynrih seeks to merge with Manik’s. This is a “little-known legend about a man with mystical powers seeking redress in the world of animals”. The nameless protagonist’s wretchedness is enticingly similar to Manik’s, and Nongkynrih, like Lieng Makaw, cannot resist.

The Distaste of the Earth

By Kynpham Sing Nongkynrih

Penguin

Pages: 480

Price: Rs.799

In the author’s hands, the two tragic heroes become one and receive spiritual succour in the non-human world. The forest folk, nonetheless, are as bitter as Manik in their misanthropy. We are given a magic real sequence in which animals take turns to reveal the deceit in man-made stories about their respective natures. They seek, and exact, revenge on Manik’s enemies and one corner of the book’s plot thus dutifully sounds an ecological warning bell. Nongkynrih believes that this mythosynthesis sheds light “on the protagonist’s inexplicable and reclusive behaviour[,] highlights the human-non-human encounter and reminds us of where our anthropocentric attitude is leading us”, thereby explaining the book’s title, although perhaps not its puzzling grammar.

The Distaste of the Earth retells a Khasi folktale of star-crossed love.

| Photo Credit:

By Special Arrangement

Nongkynrih has been said to possess an anthropologic imagination. Unfortunately, somewhere among the long lists of flora and fauna (with Latin names in parentheses), step-by-step description of rituals, painstaking sartorial anatomisation, and long-winded political debates (“Our system of governance now is monarchical in form only; in nature it is republican” is one claim), the budding shoots of epic imagination drown in a flood of ethnographic zeal.

Awkward constructions

The parallel account of the people at the liquor den framing Manik’s story is merely an adventitious appendage, revealing greater authorial interest in subaltern inclusivity than narrative art. While a book of this diversity may perhaps accommodate some unevenness in tone and register (“extispicy rites”, for instance, happily coexisting with “messed up” in the narrative voice), its ambitious thesis suffers from a distinct lack of editorial attention to detail.

Also Read | Book review: Making of India’s northeastern region

A stronger grammar and idiom check could have smoothened some of the awkward constructions and held the tonal inconsistency at bay, but the most annoying lack of editorial presence is in the foreign word policy as it relates to punctuation and typesetting. Within the same paragraph, in a speech by a single character, the same phrase is set once in italics, once without. Entire sentences in Khasi are sometimes left to speak for themselves, at other times an unpunctuated English translation follows hard on their heels, at yet other times they come capriciously swaddled in both parentheses and quotations marks. Khasi words are flung at the reader in italics at some points; elsewhere they are inexplicably cushioned in single quotes.

The story of the true love of Manik and his queen, nevertheless, still glistens like a cabochon irradiated by the truth of all great myths, irrespective of the style, material, or craftsmanship of its setting.

Debapriya Basu is Assistant Professor, English, at IIT Guwahati.